SPANISH VERSION

Kindly attended by Joe Struble, Assistant Archivist of the George Eastman Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester (New York), elrectanguloenlamano.blogspot.com had the chance to see and touch on the spot a wide range of top-notch quality original vintage copies created by four great ones in the History of Photography: Eugene Smith, Lewis Hine, Alfred Stieglitz and Julia Margaret Cameron.

The meeting took place inside the Gannett Foundation Photographic Study Center (one of the jewels of the crown of the George Eastman House Museum, the most important shrine regarding History of Photography existing on earth along with the ICP of New York), which holds an excellent assortment of works made by many famous photographers of all times, kept and preserved with exceedingly painstaking care within large special rectangular cases designed for that purpose, each one including handcraftedly manufactured copies on baryta photographic paper, made in darkroom with huge levels of thoroughness and many hours of hard work, complemented by experience to spare, good taste and love for well made things.

Joe Struble allocating with great care some copies made by Eugene Smith himself and corresponding to his very famous series called A Spanish Village, that he made in Deleitosa (Cáceres) in 1951.

The appearance of every matte black color nice rectangular case containing real masterpieces is simply superb: they´re in a perfect condition, almost brand-new, and the hinges enabling their opening and closing don´t show even the slightest scratch.

Needless to say that each case bears on the central area of its back the name of the photographer author of the pictures inside, as happened with this one titled W.Eugene Smith: A Spanish Village, which was the first shown to us by Joe Struble, and within which there were six photographs belonging to his reportage " A Spanish Village" that he fulfilled in the village of Deleitosa (Cáceres) in 1951, and where he went far beyond making a comprehensive photographic essay with 1,575 pictures, also drawing up a 24 page rundown gleaning information on that time Spain and developing a remarkable social investigation work, writing down the names and ages of all the interviewed people and managing to get a certain empathy with the photographed persons, as well as carrying out a deep socioeconomic analysis on the hard working conditions of the post civil war Spain, the high levels of illiteracy, the frequent lack of suitable hygienic conditions, etc.

The photographic essay "A Spanish Village", published by Life magazine in a special number in which seventeen pictures made by Eugene Smith were included, was an unprecedented success in the history of that publication, with a figure of more than 22,000.000 millions of copies sold, including the original issue and the subsequent reprints.

Vintage copy made by Eugene Smith from the original negative of one of his most famous images: Death in A Spanish Village, depicting the wake of Juan Larra, a just dead old man from Deleitosa (Cáceres).

The mediocre photograph made by the author of this article doesn´t make justice to the impressive quality of this truly awesome copy on baryta paper, in which you can clearly perceive that the Genius of Wichita spent a lot of hours inside his darkroom striving after giving birth to a visual score evoking as faithfully as possible the instant of image creation.

As well as being a world class photographer, Eugene Smith was an extraordinary darkroom expert who often went into seclusion for days, working up to the end of his tether, until attaining the copy he wanted, and the standard of quality he always yearned after was so high that it put the best illustrated publications during forties, fifties, sixties and seventies in a tight fix, including Life.

Another image of the table on which we can see the rectangular protective black case and by it, five of the six vintage copies it includes, made by the very Eugene Smith and belonging to his mythical photographic essay in Deleitosa (1951):" Deleitosa (Spain)" , "After a Working´s Day", "A Young Woman´s Work", "The Threader", "Death in a Spanish Village" and "Spanish Woman".

We were really amazed at the outstanding copy of "Spanish Woman", in which we can see a Deleitosa old woman wrapped into a black attire covering her whole body, with the exception of nose, cheeks, eyebrows and forehead, while two thirds of a man´s face along with his chest upper area can be seen sideways on the upper right border of the frame.

It´s a highly powerful image, with very harsh contrasts ruled by the wide and strong solar beam illuminating part of the wall behind the old woman - together with her utter face and garment- , the black colour and plates of her attire and the large vertical stripe of the image left third. Eugene Smith´s darkroom work proves to be exquisite, achieving to keep detail both on the high key areas featuring huge power and on the strong shadows, something deserving accolades, since the high keys and deep blacks existing in the moment in which Eugene Smith made this picture in Deleitosa, exceed in intensity the extraordinary photographs Portrait of the Eternal (1935), The Crouched (1934) and even Recent Tomb (1933) Manuel Alvarez Bravo´s images.

Rectangular case with a wide assortment of pictures made by Lewis Hine between 1930 and 1931 and pertaining to his famous reportage on the building of Empire State Building of New York.

This time, they were the contacts as such, created from the original negatives (13 x 18 cm) exposed with his large format 5 x 7 " (13 x 18 cm) Graflex camera, so image quality, mainly as to level of detail and tonal range was gorgeous. Not in vain, most Lewis Hine´s photographs published throughout thirties were printed using the quoted original large format negatives which allowed exceptional qualitative levels of reproduction in the illustrated publications of that period.

Perhaps the most representative example of this was Margaret Bourke-White, with her excellent large format industrial reportages made in Magnitogorsk (USSR) in 1931, without forgetting that the photographer who maybe took more advantage of the then prominent freedom of movements shooting handheld made possible with the LF Graflex camera had been Alfred Stieglitz in 1925 during the making of his series Equivalents, with a model of this brand in 4 x 5" (10 x 12 cm) format that enabled him to aim directly at the sky, liberating him from the dependance upon the tripod and being able to quickly shoot Lake George clouds in the very specific and fleeting instants he wanted to photograph.

Already thirty-five years before, he had used a large format Folmer & Schwing camera using 4 x 5" (10 x 12 cm) glass plates - which unlike his 8 x 10 " (20 x 25 cm) LF camera, didn´t need to use a sturdy tripod- and made feasible to shoot handheld, with which he made two of his most well-known pictures: The Terminal and Fifth Avenue in full winter of 1892.

The viewing of these large format Lewis Hine´s contacts framed by passe-partouts was a really unique and unforgettable experience.

Open rectangular case in horizontal position with large format vintage contacts belonging to the reportage on Empire State Building made by Lewis Hine between 1930 and 1931.

On the right, there are a lot of pictures corresponding to that mythical series, while on the left, there´s an attached sheet with lavish information on each one of the images, year and capturing location, size of the copy, etc.

The first image that can be glimpsed is the famous photograph of the Empire State Building taken from the junction of E34 Street and Madison Avenue, in which you can see the big sky scraper in the background, while a very large street lamp arises from the lower left border of the frame and soars until almost touching its upper boundary, and vast majority of vintage cars and passers-by appear blurred because of the slow shutter speed.

Nothing less than 16 vintage contacts made from large format 5" x 7" (13 x 18 cm) original negatives. Each one of them bears its own passe-partout along with a special transparent protective paper.

Unlike the previous large format cameras, which needed that the photographer made both the composition and focusing before getting the photosensitive plate inside, the large format 5" x 7" (13 x 18 cm) Graflex introduced during the first decade of XX Century and used by Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange and other photographers, enabled a much higher framing accuracy up to the very borders of the plate, and also to postpone the decisions concerning the focusing point and viewing angle until the instant of pressing the shutter release button, in such a way that security margins to thoroughly know what would finally appear inside the very big surface negatives were far superior.

Another of the main attractions of the day which made an indelible imprint in our memory: the case with 11 original vintage copies of photographs made by Alfred Stieglitz: Life and Death, Lake George (1934); Lake George Dead Tree (1930); Lake George (1925); Georgia O´Keeffe (1921); Apples and Gable, Lake George (1922); Rear view of Ford V-8 (1935); Hedges and Grasses, Lake George (1933) and Grape Leaves and House, Lake George (1934).

These works belong to his last years of images creation, in which Alfred Stieglitz almost exclusively photographed Lake George trees - his state home - with whom he identified, together with the surrounding clouds and skies that he deeply studied for a lot of hours, something which happened above all from 1923, with his mother´s demise and his daughter´s mental illness.

Albeit this was a stage in which he greatly chose not to see his works repproduced in illustrated magazines - different from what he had made during the first two decades of XX Century, one can perfectly appreciate in these flawless copies that Stieglitz went on being very exacting (specially with himself) in regard to the quality of negatives and their printing on photographic paper, scopes in which he reached international renown thanks to the extraordinary quality of reproduction of his legendary Camera Work publication,

probably the best photography magazine of all time, which existed between 1903 and 1917.

On watching Poplars, Lake George (1932) from a very short range, it dawned on us in a very lively way that the masterful allegoric visual language used by A. Stieglitz in symbiosis with a deep artistic and personal introspection when relating Lake George poplars, high trees featuring delicateness and a limited lifespan, with the perishable nature of human existence, including his own life, which began weakening. He was already almost seventy years old and he had seen these same trees grow up and getting old during the long seasons he spent in Lake George, in the Adirondack Mountains, on the Northeast of New York, where his father had bought the family mansion in 1886.

Sublime photography at its best, in which the key factors are the person behind the camera, to be in the appropriate place and moment, the quality and direction of the light, the accuracy in the timing on pressing the shutter release button, the fight to try capturing the special and shortlived atmosphere of the moment and of course the photographer´s experience.

It´s not necessary to use top of the range cameras or the most professional lenses to get good pictures, something proved for decades by many world class photographers like Ian Berry (who started his career with a medium format 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inch -6 x 6 cm- analog Zeiss Ikon Ikonta B 521/16 camera) and David Alan Harvey (who made great reportages for National Geographic using digital Nikons D70 and 100D - along with very good portraits made within very short distances for his series on Hip Hop music-) to name a few, though it isn´t less true that specific cameras and lenses feature different qualities, as happens for instance with Alex Soth and his 8 x 10 " (20 x 28 cm) large format Ebony SV810 camera with Nikkor W-300 mm f/5.6 and Copal 3 shutter, since when the camera turns into a real working tool and the photographer feels comfortable and identified with it, it´s possible to alter the way in which the world is seen, because besides, it is not the same what is attained with a large format 300 mm lens as what you get with an equivalent focal length lens in other formats.

Alfred Stieglitz began devoting intensively to the creation of pictures of trees precisely in 1932 (although he had already made his premonitory photograph Dead Tree in 1930, also in the surroundings of his family mansion ), and since then he photographed them in Lake George area from every distance and under different atmospheric and luminous conditions, something rather tangible in several of the 11 copies of Lake George series that we could see.

In spite of the perceptible grain in these amazing vintage copies on baryta paper and the usually simply acceptable quality of the lenses coupled to the cameras of the time, it doesn´t matter whatsoever when we speak about great images created by Alfred Stieglitz and many other eminent photographers who implemented their labour between 1890 and the II World War.

The emotional intensity reached indescribable peaks when after having shown us the aformentioned works by Eugene Smith, Lewis Hine and Alfred Stieglitz, Joe Struble told us that the moment had arrived to watch vintage copies of pictures made by Julia Margaret Cameron, manufactured through the albumen technique, making direct contacts from huge glass plates in sizes around 20 x 25 cm and 30 x 40 cm with a humid collodion emulsion.

Impossible to explain these moments with words. Suddenly, Joe Struble appeared with another more of the large rectangular cases, containing 9 works by the great British portrait photographer who developed her production of pictures between 1863 and 1876.

With great care and accuracy, Joe Struble, currently one of the greatest experts in the world in this sphere, is spreading out on the table the vintage copies of pictures taken by Julia Margaret Cameron, in which once more it´s distinctly revealed that the search for technical perfection was not her priority, that was essentially focused on the inception of images unmistakably unveiling the emotional state of the persons she photographed, both when they were famous men and very specially on taking pictures of women, whom she made pose with their hair loose.

Margaret Cameron´s photographs feature a romantic character, making use of subdued light and dark backgrounds to beget oniric contexts by the minute.

During her three first years of photographic yield between 1863 and 1865, Julia Margaret Cameron availed herself of a trial and error method through which she unfolded her particular technical and aesthetic grasp of photography, using a large format camera fed by 9 x 11 inches (23 x 28 cm) glass plates, overly big for the second hand Jamin Darlot Cone Centralisateur 12" (305 mm) lens and a diaphragm f/5, f/6 or f/7 (a French variation of the Petzval optical design and a viewing field similar to the one rendered by a 135 mm lens in full frame 35 mm format) attached to the box.

This objective offered exposure times between approximately 4 and 7 minutes in studio, depending on the existing luminosity, and it delivered very good sharpness in the center at normal and long distances on a narrow image field of around 35º, with noticeable curvature of field and astigmatism beyond those limits, also suffering from strong chromatic aberration, traits that made unfeasable both the depth of field control and the attainment of sharp images with an accurate focus at the very short distances which were the ones mostly used by the British photographer in her portraits (she always stroved after approaching the camera with its lens as much as possible to the head of the person posing sitting, in order that it filled the whole frame), so a high percentage of her pictures appear partially out of focus and slightly moved, for it was very difficult to get the portrayed people stay put during so many minutes of exposure, with the camera on a tripod.

Therefore, they´re portraits greatly taking advantage of the significant curvature of field and the progressive fall-off towards the image borders inherent to the Petzval optical design, which helped and helps set the attention of the observers of each photograph on the center of the image, without forgetting that the intentional design ´defects´ inserted in the optical formula of the lens, in singular synergy with its too small coverage for the size of large format glass plate it used, turn out to be decisive for the creation of uncommon portraits featuring high doses of bokeh by means of these vintage lenses made in brass, which even today go on being used by some enthusiasts of the old objectives wishing to achieve the very special Petzval image aesthetics in their pictures, besides being able to get at will an outstanding soft focus in the portraits.

The nine albumen vintage copies of Julia Margaret Cameron pictures we could see and appreciate in our hands (Beatrice, The Mountain Sweet Liberty, Mrs Herbert Duckworth (Julia Jackson), Sappho, Ophelia Study nº 2, La Madonna, Rosalba, Mrs Herbert Duckworth, and Mary Mother) were made in 1866 and 1867 with a Dallmeyer Rapid Rectilinear 30" (762 mm) f/8 lens designed to cover 18 x 22 inches (45.72 x 55. 88 cm) glass plates, but it was used by Julia Margaret Cameron attached to a large format camera using 12 x 15 inches (30.48 x 37.2 cm).

In this Dallmeyer Rapid Rectilinear 30" f/8 lens, the aberrations were much better corrected, enabling a higher control of the diaphragm aperture and depth of field, as well as being able to synergize with bigger glass plates than the ones used by the British photographer during the first three years of her career, it all with the added bonus that the optical genius John Henry Dallmeyer was also an accomplished artisan whose lenses (among the best in the photographic market between 1860 and 1900 regarding optical and mechanical quality) sported a further specially valuable trait: its remarkable consistency in results, since they were with difference the ones featuring fewer variations unit by unit, clearly beating in this side the lenses from other brands.

Whatever it may be, the debate on the pictorialist effects and the use of soft focus by Julia Margaret Cameron keeps on wholly latent, because one of the most important virtues of the glass plates with collodion is that they can yield very crisp and detailed images, albeit it isn´t less true that the British photographer managed to attain the kind of photos she wished through her then innovative and unconventional method, different from the one used by the photographers of her time.

We watch in wonderment the proficiency of Joa Struble, a great and experienced professional, making us hark back in time to the historical context around middle of XIX Century, at the height of the European Industrial Revolution, approximately 25 years after the discovery of photosensitive materials by Niepce and Daguerre. They are moments in which the albumen prints have become the first commercially viable method to make a photographic copy printed on a paper base from a negative.

This revolutionary technique for the time consisted in coating a usually 100% cotton photographic paper with an emulsion of white of egg albumen and sodium or amonic chloride, all of which was left to dry, and after it, the photographic chemicals remained fixed to the paper on which the printing was made, bringing about a slightly glossy surface on which the sensitizer rested.

It´s a hugely complex printing method and it requires great accuracy, since any little error during the making or development of the negative can affect both the appearance of the final picture and its stability and durability of the negative.

It wasn´t easy to avoid a certain trembling and quivering on holding between our hands these original albumen vintage copies made by Julia Margaret Cameron, fairly exotic, because they´re actually printed photographs more than developed, since they were born as a direct result of exposure to the light, without the help of any sort of developing solution.

On the other hand, the labour of George Eastman House Museum with regard to the preservation of these albumen vintage copies is specially praiseworthy, because they crack easily with the most feeble humidity ( owing to internal stress and hysteresis generating that the albumen layer swells and shrinks much more than most materials) and even with a very superficial cleaning, so maximum cares and safekeeping protocols are carried out.

But the Institution has got some of the most learned pundits in the world on this subject, both regarding the knowledge of the historical evolution of albumen prints of photographs made by Julia Margaret Cameron, Gustave Le Gray, Edward Muybridge, etc, and the current making of albumen copies, without forgetting other types of fascinating old procedures of printing (daguerrotypes, platinotypes, carbon printing, etc) like Mark Osterman (Historian of Classic Photographic Procedures, Director of the Kay R. Whitmore Preservation Center of the George Eastman House Museum and top authority in the domain of photography with collodion, and a consummate expert and researcher on all kind of old photographic systems, from Niepce heliographs to silver gelatin emulsions, different ways to create a passepartout on glass, use of Camera Lucida and Physionotrace, etc), France Scully Osterman (another great specialist in both photography with collodion and a wide assortment of old photographic procedures, who in the same way as Mark Osterman has developed a laudable work of teaching in the Workshops of Old Historical Photographic Procedures imparted in the George Eastman House Museum), Mark Robinson (top authority in the field of daguerreotypes , who currently uses this photographic technique in his works, achieving results which are quite up to the standard of quality of the best XIX Century artists of the daguerreotype. He works in Toronto, Canada, and gives classes and lectures on old photographic systems at Ryerson University and at the George Eastman House Museum, also being a remarkable albumen printer and current President of the Daguerre Society), Grant B. Romer (Co-Director of the Advanced Residency Program in Photograph Conservation of the George Eastman House, another world class specialist in daguerreotypes, being an outstanding consultor and curator for dealers, collectors and institutions worldwide, having been the establisher of the current conservation laboratory at the GEH since 1978), James M. Reilly (Professor of the Rochester Institute of Technology and Director of its Image Permanence Institute, also being Co-Director of the Advanced Residency Program in Photograph Conservation of the George Eastman House), Gary Albright (GEH photographic conservator featuring a 32 years experience, having also worked at the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, Massachussets) David Wooters (Archivist of the Photography Collection), Ryan Boatright ( Staff Scientist at the Image Permanence Institute of the Rochester Institute of Technology, and has imparted courses on the identification and dating of all the major photographic print systems), Bryant McIntyre (using the Leo 982 scanning electron microscope with energy dispersive X-Ray spectroscope and magnifications up to x 50,000) along with other great scholars who made a great labor at the GEH like Alice Swan ( with outstanding research made during seventies on the deterioration of daguerreotypes, treatments of conservation for photographs and very in-depth investigation on French methods and materials for colouring daguerreotypes, and while studying a famous daguerreotype image of Emily Dickinson, she managed to discover some vestiges of previous coloring on Dickinson´s forehead, on the pin and on the flowers appearing on it ), Rachel Stuhlman (Curator of Rare Books and an authority on photographically illustrated editions), Dr Fenella G. France (mastering the use of humidity detector sheets), etc, without forgetting very prominent Fellows of the Advanced Residency Program in Photograph Conservation like Ralph Wiegandt ( he was the Conservator of the Rochester Museum and Science Center in Rochester, New York and the Henry Ford Museum & Grrenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan, featuring a great expertise in both all aspects of collection care and the conservation of functional objects and scientific instruments), Fernanda Valverde (one of the most important authorities in the world on nitrate cinematographic films), Elena Simonova-Bulat (Photograph Conservator for the Mellon Photograph Preservation Programme at Havrard University Library and a pundit on the Hermitage´s daguerreotype collection), Katharine Whitman ( Photograph Conservator for the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Toronto, Canada, who has made very comprehensive research on the history and conservation of the glass supported photographs, and she was also the driving force in the investigation and conservation of a highly valuable gelatine silver interpositive glass of Abraham Lincoln printed by George B. Ayres, which was originally taken in 1860 by Alexander Hesler in Chicago, Illinois), Rosina Herrera (an expert on both paper and photograph conservation, having attended to courses given by Angel Fuentes in Spain and Ian and Angela Moor in England), Lene Grinde ( who has developed a number of restoration methods for water damaged photographic material) , and many others.

The Gannett Foundation Photographic Study Center of the George Eastman House Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester makes a point of fostering the restauration of originals and a first-rate photographic retouching. In this image, we can see some black and white vintage gelatin silver prints, made in Rochester area during thirties, ready to be retouched.

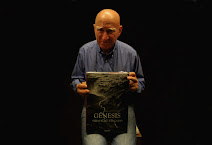

Instants before the good-bye, the great specialist on History of Photography Joe Struble poses by two photographs made by Julia Margaret Cameron and printed on albumen paper.