Text and Photos: José Manuel Serrano Esparza

The Nikon S from 1951 meant the turning point in the history of Nippon Kogaku (renamed Nikon Corporation in 1988) in particular and the Japanese photographic industry generally speaking, in spite of being clearly beaten by the following models of rangefinder cameras made by the firm during fifties:

- The Nikon S2 from 1954 which featured a larger viewfinder with a 1.0x magnification and a brilliant frame (the Nikon S viewfinder with 0.60x magnification lacked bright-line frame), better constructive materials (die-cast aluminum instead of the Nikon S sand casting aluminum), less weight (the Nikon S is built like a tank), a longer rangefinder effective base length, winding lever, rewinding crank, top shutter speed increased to 1/1000 sec, sync flash speeds dial up to 1/1000 sec and other improvements, as well as being the first Nikon rangefinder camera to be utterly redesigned to hold 24 x 36 mm film, etc.

- The

extraordinary Nikon SP from 1957. Considered the best 35 mm rangefinder camera

in history along with the Leica M3, featuring a superb eyepiece of the

viewfinder with 1x magnification that sports dual nature and keeps inside a VF

located on the right, with 1x magnification optimized for the very accurate

framing with 50, 85, 105 and 135 mm lenses -together with bright-line frames

for them all and automatic parallax correction at every distance (and another

VF with 0.4x magnification and Albada type, optimized for use with 35 mm lenses

-with bright-line frame- and 28 mm lenses - whose coverage area is made up by

the limits of this 0.4x viewfinder also integrated in the camera body-), shutter

with titanium curtains, bright-line frames adjustable for lenses between 28 and

135 mm, window showing the chosen flash synchronization speed, film counter

with autoreset system and indicator of the type of film being used.

- The Nikon S3

from 1958 and Nikon S4 from 1959.

Nikon S, the

camera which marked the start of Japanese photographic industry

international expansion. It appears here with the Nikkor-S.C 5 cm f/1.4.

And there were

some important reasons for it:

A) After checking

the great image quality rendered by a Nikkor-P.C 8,5 cm f/2 which had been

shown to him by Miki Jun (local correspondent for Life magazine in Japan) in

early May 1950, the Californian photographer Horace Bristol (a Life

photographer) went to see David Douglas Duncan (also a Life photojournalist)

who became quite surprised too on observing the very good resolving power and

superb contrast for the time that attained that lens, so after testing the

aforementioned Nikkor-P.C 8,5 cm f/2 (along with a Nikkor-S.C 5 cm f/1.5 that

likewise fascinated them) decided to visit with Jun Miki the Nippon Kogaku

factory at Ohi (Tokyo) in mid May 1950, being welcomed by Dr. Masao Nagaoka,

President of Nippon Kogaku.

That was a

revelation for both Life photographers, who made particular thorough tests and

verified that the Nikkor-P.C 8,5 cm f/2 outperformed the Zeiss Sonnar 8,5 cm f/2 in resolution and contrast, while the Nikkor-S.C 5 cm f/1.5 approached very

much to the resolving power of the Carl Zeiss Jena 5 cm f/1.5, beating it

in contrast.

Additionally,

they realized that Nippon Kogaku Japanese lenses achieved a better printing

quality on illustrated magazines, thanks to their greater contrast than highly

luminous Carl Zeiss and Leitz existing at that time, something very important

for both photojournalists, so they quickly changed their screwmount Leica

(David Douglas Duncan) and Carl Zeiss (Horace Bristol) lenses for Japanese

Nippon Kogaku ones in LTM39 thread mount and Contax bayonet respectively for

their Leica IIIc and Contax II cameras.

On June 27 1950,

David Douglas Duncan, coming from Fukuoka (a city in the south of Japan) was

the first photographer to get pictures of Korean War, equipped with two Leicas

IIIc, one coupled to a Nikkor-S.C 5 cm f/1.5 and another one attached to a

Nikkor-Q.C 13,5 cm f/3.5, both of them manufactured by Nippon Kogaku in LTM39

thread.

When David

Douglas Duncan sent his original black and white Eastman Kodak Super-XX 100 ASA

negatives developed with DK-20 in Japan to the main office of Time Life Inc. in

New York and the photomechanic tests with half tone plates were made, a great thrill

was generated because they provided excellent contrast and visual perception of

sharpness and the reproductions made from them on the luxurious paper of Life

magazine was superior regarding printing quality to all the pictures got with 35 mm

cameras and that b & w emulsion that they had handled before.

This was very

important, since the Kodak Super-XX was then the photojournalistic black and white film par

excellence, with its very high ASA 100 sensitivity for the time, which made possible to save a lot of photographs shooting handheld with available light

and highly luminous lenses, unlike the Kodak Panatomic-X b & w film, the

benchmark in terms of resolution and lack of grain, but whose very low

sensitivity of ASA 32 was not suitable for its use in agile and dynamic

photojournalism with 35 mm rangefinder cameras.

The news spread

quickly, as well as being fostered by in-depth articles appeared in Modern

Photography magazine, The New York Times (which published on December 10, 1950

an extensive report made by Hank Walker, Life photographer, on the Nikon S and

the increasing use of Nippon Kogaku lenses by professional photographers during

the Korean War), Life and the annual number of US Camera magazine from 1951

with pictures made by David Douglas Duncan with the previously quoted Japanese

lenses, in addition to the September 10, 1951 Life magazine cover in size 26,8

x 35,6 cm of the Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida with stunning

resolving power and contrast, made by Jun Miki with his Leica IIIf and a

Nikkor-P.C 8,5 cm f/2.

This is War! A

Photo-Narrative of the Korean War, lavishly illustrated with pictures made by

David Douglas Duncan during the Korean War with his Leica IIIc and Nikkor-S.C 5

cm f/1.5, Nikkor-P.C 8,5 cm f/2 and Nikkor-P.Q 13,5 cm f/3.5 . From the very first moment of

its appearance it became a reference book in the History of Photojournalism and

enhanced even more throughout decades the great international prestige of the

lenses manufactured by Nippon Kogaku for its S series rangefinder cameras,

screwmount Leicas and Contax II respectively featuring LTM39 thread mount or bayonet.

It provided

Nippon Kogaku with a huge international prestige, fostered by the fact that the

excellent for the time lenses made by the Japanese photographic firm had an

outstandingly lower price than the Zeiss and Leitz lenses sporting equivalent

focal lengths and luminosities.

This way, a

number of photographers assigned to the Korean War quickly changed their Zeiss

lenses with Contax bayonet or LTM39 thread mount Leitz ones for the Nippon

Kogaku objectives.

Advertisement of

the Nikon S and its highly luminous Nikkor lenses in full page of the Popular

Photography magazine in 1951. The headline ´ The Nikon 35 mm Embodies the Best

Features of the Most Expensive Miniatures ´ summed up the key element in the

birth of the Nikon S: Nippon Kogaku had created a rangefinder camera joining the best virtues of the Contax II and the LTM39

thread mount Leicas, with the added benefit that its Nikkor lenses beat in

optical performance in the center and specially in contrast to the equivalent

focal length objectives featuring identical widest apertures of both famous

German firms, an at a much cheaper price. It´s likewise noteworthy that still

in 1951 the cameras using 35 mm film were called miniature, because during

fifties professional photographers working with Speed Graphic 4 x 5 large

format cameras and 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ medium format Rolleiflex cameras were a broad

majority.

Another event occurred that launched Nippon

Kogaku fame even more: Carl Mydans (an extraordinary Life photographer), user

of Contax II, was sent to Korean war to complement with David Douglas Duncan

the strategic retreat of American troops to the Pusan defensive perimeter, and

Douglas Duncan insisted Mydans on acquiring Nikkor lenses for his German 35 mm

rangefinder camera.

In July 1950,

Carl Mydans visited the Nippon Kogaku factory in Ohi (Tokyo) and bought a

Nikkor-P.C 8,5 cm f/2 and a Nikkor-Q.C 13,5 cm f/3.5, both of them in Contax

mount, whose rangefinder coupling section was modified, and in 1951 he would

change his Contax II (a far superior camera from a qualitative viewpoint, much

larger effective base length and an 1x magnification viewfinder instead of

0.60x) for a Nikon S, because the latter was exceedingly robust, featured a

much more reliable shutter, its lenses delivered a superior image quality and

an amazing flawless prolonged working ability under extreme climatic

conditions.

Such factors

made that other great photographers sent by Life to the Korean War, like Hank

Walker (coverage of Incheon invasion), Margaret Bourke-White (coverage of the

operations against guerrilla units behind the line front during the stalemate

stage of the conflict) and Michael Rougier (coverage of D.W.Eisenhower visit) also

opted for the Nikon S and Nikkor lenses.

Even, Max

Desfor, an Associated Press photographer and user of Speed Graphic 4 x 5 large

format camera who covered the Korean War too, bought a Nikon S and some Nikkor

lenses, using the Nippon Kogaku camera

as a second body, which is relevant, because between 1950 and 1953 vast

majority of professional photographers on assignment in the Korean conflict (particularly

those belonging to Associated Press like George Sweers, James Martenhoff, Gene

Herrick, Jim Pringle, Fred Waters, E.N. Johnson, William Straeter, John

Randolph or Max Desfor himself) used Speed Graphic 4 x 5 large format cameras

with Kodak Ektar 127 mm f/4.7 or Raptar Wollensak 135 mm f/4.7 and Kodak Super

XX ASA 100 film or Kodak Plus-X ASA 50 film featuring a 13 times larger surface

than those same black and white emulsions in 24 x 36 mm format that were used

throughout the Korean War by the photographers who took 35 mm cameras (Leicas

IIIc and IIf, Contax II and Nikon S 24 x 34 mm) with Nikkor lenses manufactured

by Nippon Kogaku.

B) The Nippon

Kogaku optical designers had painstakingly studied both the ultraluminous Carl

Zeiss Jena Sonnar 5 cm f/1.5 and Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 8,5 cm f/2 lenses without antireflection

coating for 35 mm format previous to the II World War created by the genius

Ludwig Bertele in 1932 and 1933 and the postwar lenses sporting identical

optical formula but featuring antireflective T Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 50 mm

f/1.5, Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 85 mm f/2 (made in East Germany) and the Zeiss

Opton Sonnar 50 mm f/1.5 and Zeiss Opton Sonnar 85 mm f/2 (manufactured in West

Germany, in the city of Oberkochen) and decided to optimize as much as possible

the contrast of their new lenses for 24 x 34 mm and 24 x 36 mm format, applying

pragmatic criteria of cost savings to the utmost feasible, enhancement of

production easiness and maximum reduction of optical elements possible, not only

without reducing quality but even increasing it, which anticipated

approximately eighteen years to realistic conceptual decisions of optical

design according to market circumstances that had to be implemented by Walter

Mandler in 1969 in the Leitz factory at Midland, Ontario (Canada) with the

Summicron-R 50 mm f/2 for Leicaflex, whose optical formula reduced to 6

elements (instead of 7), simultaneously improving contrast, above all at f/2,

and augmenting image quality with respect the previous design.

Nikkor-S.C 5 cm

f/1.4, the first standard lens made in the world with such widest aperture.

Manufactured between late 1950 and 1962, nothing less than 100,000 units were

sold, a very significant figure for the time, and replaced the Nikkor-S.C 5 cm

f/1.5 also featuring 7 elements in 3 groups and 12 diaphragm blades, which was

launched into market in May 1950 and would be the Nikkor standard lens used by

David Douglas Duncan since late June 1950 during the Korean War. The making by

Nippon Kogaku of these two standard 50 mm lenses along with the Nikkor P.C 8,5

cm f/2, only five years after the end of the II World War in which Japanese

industry had been greatly leveled, and using handcrafted working parameters

with very scarce economical means and materials is one of the greatest feats in

the History of Photography.

Although it had

experimental furnaces for the melting of crystal for obtaining optical glasses

and a Naxos-Union machine acquired in Germany in 1922 and able to grind optical

elements, and even had set up an optical glass research facility in one of the

areas of its factory at Shanagawa (in the south of Tokyo) in 1923, during the

late forties and first years of fifties, Nippon Kogaku, being aware that hadn´t

got the wherewithal, technical means, updated machinery, computers or optical

glasses combining very high refractive indexes and low chromatic dispersion to

be able to get with an acceptable production cost a high uniformity of

top-notch performance as to resolving power and contrast in center, borders and

corners at every diaphragm and focusing distance (something that wouldn´t be

possible until 1956 with the appearance of the Summicron-M 50 mm f/2 Dual range

featuring 7 elements -four of them being the very expensive LaK9- in 5 groups

and the Asahi Pentax Auto-Takumar 55 mm f/1.8 sporting 6 elements in 5 groups

with M42 thread mount in 1958- though the latter rendering less contrast than

the Nikkor-S.C 5 cm f/1.4 and Nikkor P.C 8,5 cm f/2-) chose to apply a

practical criterion and achieve full operativeness in its Nikkor f/1.5, f/1.4,

f/2 and f/3.5 at maximum aperture with an acceptable image quality that became

superb for the time on stopping down two diaphragms.

Nikon S advertisement in full page inside the U.S Camera magazine of 1951, commending the optical and mechanical virtues of the Nippon Kogaku Rangefinder System of Cameras, Lenses and Accessories. It greatly fostered the Japanese brand leverage within the worldwide photographic market.

Top priority was given to both contrast and resolution in the center of the frame and using a very high quality antireflective monocoating with blue tonality which was the evolutive summit of a wide range of antireflection coatings that Nippon Kogaku had been manufacturing since mid twenties in different very high quality optical instruments for the Japanese Imperial Navy and that had turned the Ohi (Shinagawa, Tokyo) based optical firm into the world benchmark regarding this side from mid forties (even ahead of the Carl Zeiss monocoatings based on Alexandr Smakula fundamental principles which had been secretly developed by Germany during World War II), yet had only been applied to large size optical contrivances for the Japanese Imperial Navy, specially the ones manufactured for submarines periscopes, hugely resistant to the most adverse environment conditions and whose evolved formulae were used in the optical elements of Nikkor lenses from 1948 on, so currently the antireflective monocoatings of most photographic lenses for 24 x 36 mm made during late forties and fifties by Nippon Kogaku are often in very good condition, more than sixty years after their creation.

Nikon S advertisement in full page inside the U.S Camera magazine of 1951, commending the optical and mechanical virtues of the Nippon Kogaku Rangefinder System of Cameras, Lenses and Accessories. It greatly fostered the Japanese brand leverage within the worldwide photographic market.

Top priority was given to both contrast and resolution in the center of the frame and using a very high quality antireflective monocoating with blue tonality which was the evolutive summit of a wide range of antireflection coatings that Nippon Kogaku had been manufacturing since mid twenties in different very high quality optical instruments for the Japanese Imperial Navy and that had turned the Ohi (Shinagawa, Tokyo) based optical firm into the world benchmark regarding this side from mid forties (even ahead of the Carl Zeiss monocoatings based on Alexandr Smakula fundamental principles which had been secretly developed by Germany during World War II), yet had only been applied to large size optical contrivances for the Japanese Imperial Navy, specially the ones manufactured for submarines periscopes, hugely resistant to the most adverse environment conditions and whose evolved formulae were used in the optical elements of Nikkor lenses from 1948 on, so currently the antireflective monocoatings of most photographic lenses for 24 x 36 mm made during late forties and fifties by Nippon Kogaku are often in very good condition, more than sixty years after their creation.

In addition, it

must be mentioned the remarkable inventiveness and intuition of Nippon Kogaku mechanical engineers, who

provided the horizontal travelling plano-focal shutter of the Nikon S (whose

curtains were made with rubberized Habutae silk on both surfaces, inspired by

the one featured by screwmount Leicas, designed by Dr. Ludwig Leitz and whose

curtains were made of silk cloth) with a back curtain tooth placed on a ball

bearing whose rotation smoothness proved to be very efficient for the perfect

functioning of the camera even at temperatures of -30º C.

And all of this

deserves high accolades, because between 1946 and mid fifties, Nippon Kogaku had

to work with rather scant economic resources and nothing short of a permanent

dearth of materials that they compensated by dint of great optical experience,

A Nikkor lens is

examined by an expert Japanese technician inside the Nippon Kogaku factory at Ohi

(Tokyo) on January 5, 1952. © Photo AP Bob Schutz

impressive

greatly manual unit by unit working ability, ingenuity to spare, fullest use of

the few available means and widest possible utilization of the great optical

know-how gained throughout roughly twenty-five years manufacturing all kind of

top quality optical instruments and opto-mechanic components for the Imperial

Navy.

The Japanese,

great admirers of the German photographic industry (particularly Carl Zeiss and

Leica, its two more prominent firms), had started their photographic way to

great extent since 1929 when Kakuya Sunayama became the key optical designer of

the Ohi (Tokyo) based firm after the experience acquired (regarding formulation

of lenses for photographic cameras, polishing and grinding of optical elements,

mechanical assemblies, etc) in contact with the seven proficient optical

designers and mechanic engineers from Zeiss who had been hired by Nippon Kogaku

in 1921 and remained in Japan throughout five years, and specially through the teachings imparted by the engineer and

optical designer Heinrich Acht (who would prolong his stay in Japan until

1928), it all being complemented by a European learning tour made by Sunayama

in the second half of 1928 and early 1929, during which he visited the Leitz

factory in Wetzlar, some Zeiss facilities, the Taylor-Hobson factory in

Leicester (England) and some further optical factories in Holland and France,

watching on the spot the different techniques of lenses manufacturing used,

systems of series production, quality controls and so forth.

C) The creation of

the Laboratory for Optical Precision Instruments by Saburo Uchida, Takeo Maeda

and Goro Yoshida in November 1933 had resulted in the first Japanese rangefinder

35 mm camera, the Kwanon prototype from 1934, and the Hansa Canon Standard

Model from 1935, inspired by the Leica II (Model D) from 1932.

The Hansa Canon

Standard Model from 1935 featured an optical viewfinder system integrated with

a coincidence rangefinder, a mount for interchangeable lenses (made by the

mechanic engineer Eiichi Yamakana) and a Nikkor 50 mm f/3.5 standard lens

(created by Kakuya Sunayama) that had been designed and manufactured by Nippon

Kogaku, which had been asked for help by the firm Seiki Kogaju - future Canon -

, something that had outstandingly enhanced the image of Ohi (Tokyo) concern

since mid thirties, in such a way that after Nippon Kogaku made its first 24 x

32 mm camera Nikon I in 1948 and the Nikons M and M Sync in 1950, the arrival

of the Nikon S (whose bayonet mount is very similar to the Hansa Canon) meant

the complete consolidation of the firm´s cameras and lenses division.

D) The huge rangefinders

in synergy with the main and secondary artillery of the superbattleship Yamato,

whose building was ordered by the Japanese Imperial Navy to Nippon Kogaku in

early 1937.

The largest of

them, whose size was 15 m, was located in the top area of the high structure in

pagoda of the bridge

and was by far

the world optical state-of-the-art in this kind of exceedingly accurate

devices, being able to make that this ship, the most powerful of its class ever

made, could zero in on enemy warships at a distance of 40 km with its main

naval artillery made up by three turrets with 18 inch (46 cm) guns, two of them

being fore and one astern, each one holding on its turn a further 15 meter

rangefinder (whose ends protrude on both sides of the turres) which enabled to

keep on independent accurate shots solutions with amazing precision if the main

15 m rangefinder placed on top of the high structure in pagoda of the bridge

was damaged.

The system of

optical elements and groups of this massive rangefinder (whose specifications

were kept in the utmost secrecy until the sinking of Yamato battleship by the

United States naval air force on April 7, 1945 during its approach to Okinawa island and also

hitherto) was at the forefront of innovation in its time, sporting a great

technical complexity and attained an outstanding accuracy - which made up for

the inferiority of the Japanese Navy flagship with respect to the electronic

radar guided MK 38 GFCS system of main artillery fire control on board of the

American class Iowa battleships - , complemented by a further rangefinder

measuring 10 meters, located just behind the large battleship chimney, likewise

boasting an extraordinary optical level and which directed the fire of each one

of the two secondary artillery turrets having three 155 mm guns, each of them holding a

7,5 meter rangefinder.

After the end of

the II World War in September 1945, and though all the existing drawings

(including the ones depicting its optical system of fire direction featuring the

two aforementioned 15 meter and 10 meter rangefinders, along with the other

three of 15 meters and two further ones of 7,5 meters) were destroyed, the whole

impressive know-how and optical experience gained during the development of

those fabulous rangefinders together with the breakthrough advances in

opto-mechanical precision engineering introduced in their prisms were inside

the head of some Nippon Kogaku experts who had collaborated in their development

and used a few years later some of the technical resources set up in them for

the first time - hugely reducing both optical and mechanic components to a

miniaturized scale- for the birth of the Nippon Kogaku cameras rangefinders

from 1948, with a number of budgetary constraints (it was impossible to create cameras

sporting such a wide rangefinder effective base length like the Contax II and a

1x viewfinder magnification that would have shot up the series production

costs) that compelled in the beginning to design rangefinders getting good

accuracy but being simple and not very expensive to build - with a moderate

effective base and 0.60 x VF magnification- for the Nikon I (1948), Nikon M

and M Sync (1950) and Nikon S (1951), but after the beginning of the great

international sales from 1953 and the obtaining of a significant cashflow, in

1954 Nippon Kogaku launched into market the Nikon S2, a far better camera than

the Nikon S and boasting a rangefinder with larger effective base length and a

1x VF magnification.

Three years

later, in 1957, an even greater percentage of the wealth of knowledge acquired

during the development of the rangefinders of Yamato battleship was

miniaturized and transferred to the excellent rangefinder boasting a wide

effective base length and a viewfinder of great quality and complexity

featuring a 1x magnification and incorporating 28 optical elements, located in

the right area of the eyepiece, with bright-line frames for 50, 85, 105 and 135

mm (which are selected by the photographer turning the big dial with black

background and figures 5, 8.5, 10.5 and 13.5 placed on the upper left area of

the camera around the rewind crank) featuring automatic parallax correction,

and a second separated viewfinder, of Albada type, sporting a smaller

magnification - 0.4x - and being in the left area of the eyepiece, whose window

indicates the 28 mm frame, as well as having a built-in bright-line frame

encompassing the image area covered by a 35 mm lens - without automatic

parallax correction - , with which the Nikon SP enables the very accurate use

of nothing less than six focal lengths: 28, 35, 50, 85, 105 and 135 mm.

E) The visionary

nature of Joe Ehrenreich, President of Ehrenreich Photo-Optical Industries

(EPOI), who in 1953 reached an agreement with Nippon Kogaku Tokyo and began

importing the Nikon S and highly luminous Nikkor lenses to United States,

making an indefatigable labour together with his team made up by Herbert Sax (

a highly experienced man in the scope of photographic equipments quality

controls) and Joseph K. Abbot (a very knowledgeable professional in finance and

marketing), making the brand known and getting big sales figures, in such a way

that that between 1951 and 1955 a total of 37,000 Nikon S cameras were sold

worldwide (a very important figure for the time), United States being the

country in which most of them were sold.

Ehrenreich

realized from scratch that the quality/price ratio of the cameras and lenses

made by Nippon Kogaku was virtually unbeatable at those moments (from 1954

onwards the formidable Leica M3 would become the opto-mechanical qualitative

benchmark, but at a much higher price than the Japanese rangefinder cameras) and

grasped the immense future possibilities of those Japanese products,

particularly among the professional photographers, to such an extent that he strengthened

the concept of after sales support and counseling to customers by the firm,

set up Nippon Kogaku centers in the most significant arenas of different sports

in which EPOI lent Nikkor telephoto lenses, and even travelled to Japan

twice a year to report the Nippon Kogaku top directors on the improvements

suggested by professional photojournalists with whom he was in steady contact.

F) Robert Capa was

wearing hanging on his chest a Nikon S camera with Nikkor-S.C 5 cm f/1.4 with

which he made around 14:55 h of May 24, 1954

his last colour

picture with Kodachrome K-11 ISO 12 film when he was advancing around 3

kilometers from Than Né, province of Thai Binh (Vietnam), with a French column

in retreat, a few seconds before dying when stepping on a mine, and in which

can be seen seventeen soldiers of the French column (one of them, located on

the left of the image, is wearing a campaign radio, while the one placed on the

right and nearest to the camera has got a mine detector), and in the

background, slightly on the right of the image, a tank can be glimpsed.

Capa had been

invited to Japan by Mainichi editorial in April 1954 to get pictures for

illustrating a new magazine that they were going to launch, and Nippon Kogaku

took advantage of that chance to deliver him five Nikon S cameras and

fifteen lenses, along with abundant rolls of 35 mm colour film, to test all of

the material, which he made, getting above all pictures of children, until

Charles Raymond Macklan, picture editor of Life, asked him to go to cover the

Indochina War between France and the Vietminh during four weeks, replacing

Howard Sochurek.

At the moment of

the explosion, Capa had two cameras, a Contax IIa with Carl Zeiss Jena 5 cm f/2

with which he made the last picture of his life, in black and white one, just

before dying, and the mentioned Nikon S with Nikkor-S.C 5 cm f/1.4 lens that was

sent flying through the air up to a distance of some meters.

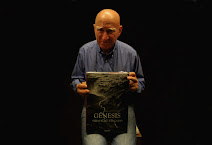

The Complete Nikon Rangefinder System, a reference work written by Robert Rotoloni, a great authority in the Nikon rangefinder system and President of the Nikon Historical Society. This extraordinary book, edited in 2007, is the fruit of more than 30 years of research and was launched into market 25 years after the first 1982 edition. It features nothing more than 548 pages, including 1,350 black and white illustrations and 24 pages with colour images made by the photographer Tony Hurst. It´s undoubtedly an indispensable book for any enthusiast of photography who wishes to delve into the knowledge of the fascinating history of Nippon Kogaku along with its cameras, lenses and accessories.

The amazing Nikon RF System of Cameras, Lenses and Accessories has been kept alive for a lot of decades specially thanks to the praiseworthy labour of the NHS and its world class experts like Robert J. Rotoloni, Uli Koch, Hans Braakhuis, Stephen Gandy, Hans Ploegmakers, Yutaka Ohtsu, Bill Kraus, Yuki Kawai, Wes Loder, Dr. Milos Mladek, Tom Abrahamsson, Akihiko Suzuki, Bob Rogen, Thierry Ravassod, Jim Emmerson and others, along with the also laudable work of the Nikon Kenkyukai Tokyo and its knowledgeable Nikon authorities like Dr. Ryosuke Mori, Dr. Manabu Nakai, Shoichiro Yoshida, Mikio Itoh, Hirosi Kosai, Dr. Zyun Koana, Akito Tamla, Michio Akiyama and others.

© Text and Photos: José Manuel Serrano Esparza

The Complete Nikon Rangefinder System, a reference work written by Robert Rotoloni, a great authority in the Nikon rangefinder system and President of the Nikon Historical Society. This extraordinary book, edited in 2007, is the fruit of more than 30 years of research and was launched into market 25 years after the first 1982 edition. It features nothing more than 548 pages, including 1,350 black and white illustrations and 24 pages with colour images made by the photographer Tony Hurst. It´s undoubtedly an indispensable book for any enthusiast of photography who wishes to delve into the knowledge of the fascinating history of Nippon Kogaku along with its cameras, lenses and accessories.

The amazing Nikon RF System of Cameras, Lenses and Accessories has been kept alive for a lot of decades specially thanks to the praiseworthy labour of the NHS and its world class experts like Robert J. Rotoloni, Uli Koch, Hans Braakhuis, Stephen Gandy, Hans Ploegmakers, Yutaka Ohtsu, Bill Kraus, Yuki Kawai, Wes Loder, Dr. Milos Mladek, Tom Abrahamsson, Akihiko Suzuki, Bob Rogen, Thierry Ravassod, Jim Emmerson and others, along with the also laudable work of the Nikon Kenkyukai Tokyo and its knowledgeable Nikon authorities like Dr. Ryosuke Mori, Dr. Manabu Nakai, Shoichiro Yoshida, Mikio Itoh, Hirosi Kosai, Dr. Zyun Koana, Akito Tamla, Michio Akiyama and others.

© Text and Photos: José Manuel Serrano Esparza

The author wishes to express his gratitude to Mariano Pozo Ruiz, who kindly lent his Nikon S camera for the making of the pictures illustrating this article.

+NIKON+S+WITH+NIKKOR+S.C+5+CM+F1.4+AERIAL+DIAGONAL+RIGHT+VIEW.+Photo+Jos%C3%A9+Manuel+Serrano+Esparza.jpg)

+NIKON+S+WITH+NIKKOR+S.C+5+CM+F1.4.+LYING+TOP+VIEW.+Photo+Jos%C3%A9+Manuel+Serrano+Esparza.jpg)

+ON+JANUARY+5,+1952.+Photo+AP+Bob+Schutz.jpg)