ENGLISH

Tumba de Robert Capa en el Cementerio de Amawalk (Nueva York).

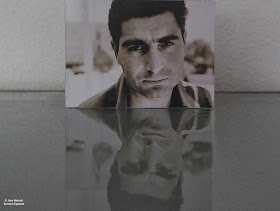

Hoy se cumple el Centenario del Nacimiento de Robert Capa (Budapest, 22 de Octubre de 1913), uno de los más importantes fotógrafos de la Historia, genuino representante del fotoperiodismo de guerra que hizo muchas fotografías extraordinarias en cinco conflictos bélicos (Guerra Civil Española, Segunda Guerra Chino-Japonesa, Segunda Guerra Mundial en Europa, Guerra Árabe-Israelí de 1948 y Primera Guerra de Indochina), fundador de la Agencia Magnum y un hombre cuya constante defensa de sus compañeros de profesión a través del concepto de la preservación de los negativos originales y su tenencia en propiedad por los fotógrafos autores de las imágenes habría de revolucionar el fotoperiodismo moderno.

Hoy se cumple el Centenario del Nacimiento de Robert Capa (Budapest, 22 de Octubre de 1913), uno de los más importantes fotógrafos de la Historia, genuino representante del fotoperiodismo de guerra que hizo muchas fotografías extraordinarias en cinco conflictos bélicos (Guerra Civil Española, Segunda Guerra Chino-Japonesa, Segunda Guerra Mundial en Europa, Guerra Árabe-Israelí de 1948 y Primera Guerra de Indochina), fundador de la Agencia Magnum y un hombre cuya constante defensa de sus compañeros de profesión a través del concepto de la preservación de los negativos originales y su tenencia en propiedad por los fotógrafos autores de las imágenes habría de revolucionar el fotoperiodismo moderno.

Pero Robert Capa jamás se consideró el mejor

fotógrafo de guerra del mundo.

Tal denominación le fue otorgada en 1938 por

Stefan Lorant, director y editor gráfico de Picture Post, tras la publicación de sus soberbias

fotos de la batalla del río Segre con obuses estallando alrededor, pero él

nunca se sintió a gusto con tal calificativo, ya que tenía un respeto muy

profundo por sus compañeros de profesión, entre los que se encontraban

monstruos de la talla de Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Eugene

Smith, David Seymour Chim, Werner Bischof, Ernst Haas, Carl Mydans, Elliot Elisofon y muchos

otros.

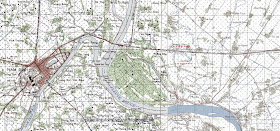

5:45 h de la madrugada. Amanece en Thahn Né, Región de Kien Xuong, Provincia de Thai Binh (Vietnam). En un gran arrozal situado a tres kilómetros de este municipio murió Robert Capa el 25 de Mayo de 1954.

No obstante, su estilo de fotografiar enormemente ágil y dinámico, intentando siempre estar en el lugar adecuado en el momento adecuado, acercándose lo máximo posible a las personas y contextos que fotografiaba arriesgando frecuentemente la vida, su ardua lucha permanente por captar las imágenes desde los más diversos ángulos posibles plasmando los instantes más representativos, su profundo amor por las gentes de todos los países en que trabajó, su sincera empatía y compromiso con los seres humanos a los que inmortalizó con sus cámaras captándoles frecuentemente en situaciones dramáticas, de miseria, angustia, incertidumbre, miedo a la muerte, máxima necesidad, etc, le convirtieron en el arquetipo de una nueva especie de fotógrafo de guerra que trabajaba a gran velocidad y con un timing muy preciso con las nuevas cámaras “formato miniatura” de 35 mm Leica (entre 1932 y mediados de Mayo de 1937) y Contax (entre finales de Mayo de 1937 y Mayo de 1954), si bien su notable versatilidad le permitió también usar a gran nivel la Rolleiflex binocular de formato medio 6 x 6 cm (a partir de 1939).

Imágenes como las de León Trotsky Durante su Discurso en Copenhague en 1932; las de la Arenga a los Milicianos en la Finca de Villa Alicia por dos jefes anarquistas al mediodía del 5 de Septiembre de 1936 animándoles para la batalla poco antes de entrar en combate; su cobertura de la Huída de los Refugiados de Cerro Muriano por la salida norte del pueblo ante el bombardeo franquista; la icónica instantánea del Miliciano Abatido; sus impresionantes imágenes cerca de Fraga (Frente de Aragón) durante la Ofensiva Republicana en el Río Segre en 1938 captando la explosión de los obuses de artillería franquista que estallan a muy pocos metros de donde se halla ubicado jugándose la vida y en las que casi puede percibirse el olor de la pólvora; la Mujer que Corre Junto a su Perro para Refugiarse del Bombardeo Aéreo de Barcelona en Enero de 1939; la Huída de Refugiados Catalanes a Través de la Carretera de Barcelona a Tarragona (incluyendo las dantescas imágenes de la anciana aturdida que camina alrededor de su carro atacado por aviones italianos en vuelo rasante y que han matado a todos sus familiares, así como a dos mulas y un perro); los Refugiados Yendo a Pie a Través de la Carretera de Barcelona a la Frontera Francesa; su reportaje en los Campos de Refugiados de Argelès-sur-Mer y Le Barcares en Marzo de 1939; la primera oleada atacando Omaha Beach el Día D 6 de Junio de 1944 bajo las balas alemanas, con muchos soldados americanos muriendo a su alrededor mientras hace las fotos arriesgando la vida en todo momento; el Jovencísimo Soldado Americano que Maneja una Ametralladora en el Balcón de una Casa de Leipzig y Resulta Muerto de un Balazo en la Cabeza por un Francotirador Alemán el 18 de Abril de 1945; sus fabulosas fotografías hechas a Pablo Picasso en su Estudio de París en Septiembre de 1944; sus imágenes en Rusia y Ucrania durante su Viaje con John Steinbeck en Agosto y Septiembre de 1947; su serie en el Kibbutz de Negba (Israel) en 1949; la Niña que Llora a la Izquierda de la Imagen en el Campamento Temporal para Inmigrantes en Sha ´arha ´aliya, Haifa (Israel) en 1950; los Inmigrantes Invidentes y sus Familias cerca de Gedera (Israel) en Noviembre-Diciembre de 1950; sus entrañables fotografías de Niños en Tokio, Osaka, Nara y Atami en Abril de 1954; la Joven Mujer Vietnamita desconsolada que Sujeta a su Niño Pequeño Mientras Llora junto a la Tumba de su Marido en un Cementerio Militar y muchas otras (la lista sería enorme) constituyen en sí mismas documentos gráficos de excepcional valor que testimonian muchos momentos de trascendental importancia del siglo XX y mayormente lo que en realidad es la guerra y sus consecuencias para los seres humanos que la padecen.

5:45 h de la madrugada. Amanece en Thahn Né, Región de Kien Xuong, Provincia de Thai Binh (Vietnam). En un gran arrozal situado a tres kilómetros de este municipio murió Robert Capa el 25 de Mayo de 1954.

No obstante, su estilo de fotografiar enormemente ágil y dinámico, intentando siempre estar en el lugar adecuado en el momento adecuado, acercándose lo máximo posible a las personas y contextos que fotografiaba arriesgando frecuentemente la vida, su ardua lucha permanente por captar las imágenes desde los más diversos ángulos posibles plasmando los instantes más representativos, su profundo amor por las gentes de todos los países en que trabajó, su sincera empatía y compromiso con los seres humanos a los que inmortalizó con sus cámaras captándoles frecuentemente en situaciones dramáticas, de miseria, angustia, incertidumbre, miedo a la muerte, máxima necesidad, etc, le convirtieron en el arquetipo de una nueva especie de fotógrafo de guerra que trabajaba a gran velocidad y con un timing muy preciso con las nuevas cámaras “formato miniatura” de 35 mm Leica (entre 1932 y mediados de Mayo de 1937) y Contax (entre finales de Mayo de 1937 y Mayo de 1954), si bien su notable versatilidad le permitió también usar a gran nivel la Rolleiflex binocular de formato medio 6 x 6 cm (a partir de 1939).

Imágenes como las de León Trotsky Durante su Discurso en Copenhague en 1932; las de la Arenga a los Milicianos en la Finca de Villa Alicia por dos jefes anarquistas al mediodía del 5 de Septiembre de 1936 animándoles para la batalla poco antes de entrar en combate; su cobertura de la Huída de los Refugiados de Cerro Muriano por la salida norte del pueblo ante el bombardeo franquista; la icónica instantánea del Miliciano Abatido; sus impresionantes imágenes cerca de Fraga (Frente de Aragón) durante la Ofensiva Republicana en el Río Segre en 1938 captando la explosión de los obuses de artillería franquista que estallan a muy pocos metros de donde se halla ubicado jugándose la vida y en las que casi puede percibirse el olor de la pólvora; la Mujer que Corre Junto a su Perro para Refugiarse del Bombardeo Aéreo de Barcelona en Enero de 1939; la Huída de Refugiados Catalanes a Través de la Carretera de Barcelona a Tarragona (incluyendo las dantescas imágenes de la anciana aturdida que camina alrededor de su carro atacado por aviones italianos en vuelo rasante y que han matado a todos sus familiares, así como a dos mulas y un perro); los Refugiados Yendo a Pie a Través de la Carretera de Barcelona a la Frontera Francesa; su reportaje en los Campos de Refugiados de Argelès-sur-Mer y Le Barcares en Marzo de 1939; la primera oleada atacando Omaha Beach el Día D 6 de Junio de 1944 bajo las balas alemanas, con muchos soldados americanos muriendo a su alrededor mientras hace las fotos arriesgando la vida en todo momento; el Jovencísimo Soldado Americano que Maneja una Ametralladora en el Balcón de una Casa de Leipzig y Resulta Muerto de un Balazo en la Cabeza por un Francotirador Alemán el 18 de Abril de 1945; sus fabulosas fotografías hechas a Pablo Picasso en su Estudio de París en Septiembre de 1944; sus imágenes en Rusia y Ucrania durante su Viaje con John Steinbeck en Agosto y Septiembre de 1947; su serie en el Kibbutz de Negba (Israel) en 1949; la Niña que Llora a la Izquierda de la Imagen en el Campamento Temporal para Inmigrantes en Sha ´arha ´aliya, Haifa (Israel) en 1950; los Inmigrantes Invidentes y sus Familias cerca de Gedera (Israel) en Noviembre-Diciembre de 1950; sus entrañables fotografías de Niños en Tokio, Osaka, Nara y Atami en Abril de 1954; la Joven Mujer Vietnamita desconsolada que Sujeta a su Niño Pequeño Mientras Llora junto a la Tumba de su Marido en un Cementerio Militar y muchas otras (la lista sería enorme) constituyen en sí mismas documentos gráficos de excepcional valor que testimonian muchos momentos de trascendental importancia del siglo XX y mayormente lo que en realidad es la guerra y sus consecuencias para los seres humanos que la padecen.

ULTIMAS HORAS DE VIDA DE CAPA EN VIETNAM Y LUGAR DE

SU MUERTE

24

de Mayo de 1954. Procedente del aeropuerto de Gia Lam en Hanoi, Capa acaba de

llegar a la base aérea de Nam Dinh ubicada a las afueras sur de esta ciudad ( 72 kilómetros al sureste de la capital de Vietnam del Norte) a

bordo de un pequeño avión Morane Saulnier MS-500 Criquet de enlace, con motor Argus As 10 de 8 cilindros y 240 caballos de potencia fabricado en Francia, en compañía de John Mecklin (corresponsal de

Time) y el general René Cogny, comandante de las fuerzas galas en Vietnam

del Norte.

Pese a la corta distancia existente entre ambas ciudades, se ha optado por el transporte aéreo de ambos periodistas y del alto oficial para evitar los riesgos que supondría el viaje por tierra, ya que el Vietminh está muy activo en las zonas de Thu´o´ng Tin, Cao Cuán, Phú Xuyén, Hu´ng Yên, Duy Tiên, Kim Báng, Lý Nhân, Hanh Liêm y Binh Luc, que jalonan de norte a ligeramente sureste el espacio que las separa, y los altos mandos franceses desean garantizar al máximo posible la seguridad de los tres (Donald M. Wilson, corresponsal de Life magazine en Indochina y que había acompañado a Capa en Laos entre el 10 y el 16 de Mayo de 1954 durante la cobertura del traslado de heridos graves franceses en helicópteros procedentes de Diem Bien Phu y que fueron a continuación llevados en aviones a Hanoi para ser tratados, había cedido su asiento a John Mecklin, porque la pequeña aeronave sólo tenía dos plazas disponibles para reporteros y además tenía varias crónicas pendientes de mecanografiar para la oficina de Life en Nueva York).

El general René Cogny fotografiado por Robert Capa en el interior del avión Morane Saulnier MS-500 Criquet durante el vuelo desde Hanoi a Nam Dinh el Lunes 24 de Mayo de 1954, pocos minutos antes de aterrizar en la base aérea francesa de Nam Dinh. © Robert Capa / ICP New York

Así pues, el aparato Morane-Saulnier MS-500 aterriza en la base aérea francesa ubicada pocos kilómetros al sur de Nam Dinh, y desde allí, Capa, Mecklin y el general René Cogny se dirigen en coche a la ciudad de Nam Dinh,

Pese a la corta distancia existente entre ambas ciudades, se ha optado por el transporte aéreo de ambos periodistas y del alto oficial para evitar los riesgos que supondría el viaje por tierra, ya que el Vietminh está muy activo en las zonas de Thu´o´ng Tin, Cao Cuán, Phú Xuyén, Hu´ng Yên, Duy Tiên, Kim Báng, Lý Nhân, Hanh Liêm y Binh Luc, que jalonan de norte a ligeramente sureste el espacio que las separa, y los altos mandos franceses desean garantizar al máximo posible la seguridad de los tres (Donald M. Wilson, corresponsal de Life magazine en Indochina y que había acompañado a Capa en Laos entre el 10 y el 16 de Mayo de 1954 durante la cobertura del traslado de heridos graves franceses en helicópteros procedentes de Diem Bien Phu y que fueron a continuación llevados en aviones a Hanoi para ser tratados, había cedido su asiento a John Mecklin, porque la pequeña aeronave sólo tenía dos plazas disponibles para reporteros y además tenía varias crónicas pendientes de mecanografiar para la oficina de Life en Nueva York).

El general René Cogny fotografiado por Robert Capa en el interior del avión Morane Saulnier MS-500 Criquet durante el vuelo desde Hanoi a Nam Dinh el Lunes 24 de Mayo de 1954, pocos minutos antes de aterrizar en la base aérea francesa de Nam Dinh. © Robert Capa / ICP New York

Así pues, el aparato Morane-Saulnier MS-500 aterriza en la base aérea francesa ubicada pocos kilómetros al sur de Nam Dinh, y desde allí, Capa, Mecklin y el general René Cogny se dirigen en coche a la ciudad de Nam Dinh,

siendo recibidos por Jean Lacapelle, jefe del sector francés, que les sugiere que le acompañen al día siguiente durante una misión de repliegue de fuerzas que consistirá en evacuar y destruir los pequeños fuertes franceses de Doaithan y Thanhne, ubicados en el extremo sureste del Distrito de Kien Xuong en la Provincia de Thai Binh, muy cerca ya de la frontera con el Distrito de Tien Han.

Poco después, Capa asiste a una importante reunión dentro del Cuartel General Francés en Nam Dinh, donde hace fotografías del general René Cogny y el coronel Paul Vanuxen estudiando en varios mapas la situación de la zona en ese momento. A diferencia de tres años antes cuando Jean de Lattre de Tassigny pudo defender la ciudad moviendo tres brigadas acorazadas, consiguiendo frenar las acometidas del Viet Minh y sus líneas de aprovisionamiento el 6 de Junio de 1953, preservando el control del Delta del Río Rojo (Hông Sông), ahora los altos oficiales galos saben que el cambio de estrategia de Nguyên Giáp (de oleadas humanas de asalto a guerra de guerrillas de atrición encaminada a la prolongación del conflicto y el paulatino desgaste del enemigo, potenciada por movimientos muy sigilosos de tropas hacia los puntos de emboscadas, produciendo la mayor cantidad de bajas posibles al enemigo con ataques muy rápidos en zonas óptimas elegidas con anterioridad, evitando la detección por tierra o aire, y dispersándose con enorme rapidez durante la retirada) está teniendo éxito y las fuerzas del Viet Minh controlan la mayor parte de las zonas rurales en el Delta del Río Rojo (Hông Sông).

A partir de ahora, el plan del alto mando galo va a consistir en abandonar las pequeñas guarniciones francesas situadas en zonas rurales, imposibles de defender ante las tácticas de guerrilla y el profundo conocimiento del terreno por parte del Vietminh y concentrar sus esfuerzos en las ciudades importantes.

Por la tarde, Capa y Mecklin van en coche al pueblo

de Phu Ly, situado unos 40 km al oeste de Nam Dinh, donde son informados por

soldados franceses de que el Viet Minh está tomando el control del área y

realiza frecuentes incursiones.

Por la noche, una vez de regreso en Nam Dinh, se

hospedan en una destartalada pensión denominada Hotel Moderno, donde se

encuentran con Jim Lucas, corresponsal de Scripps-Howard, a quien Capa había

conocido en Hanoi.

25

de Mayo de 1954.

A las 7:00 h de la mañana, Capa, Mecklin y Lucas

suben a un jeep del ejército francés que les espera junto a la puerta del Hotel

Moderno y se dirigen a las afueras noreste de Nam Dinh dirección Thai Binh.

Pocos kilómetros más adelante, aguardan junto a un tramo del río Rojo (Sông Hông) a que la fuerza francesa formada por 2.000 hombres y 200 vehículos a motor (incluyendo camiones, jeeps y tanques) sea transbordada en ferry al otro lado de esta gran vía fluvial.

Tras cruzar el río, la columna de tropas francesas avanza en dirección a la Provincia de Thai Binh, internándose en su región de Vu Thu, y aproximadamente a las 8:40 h de la mañana

son atacados en el tramo de carretera entre Bong Dien y Nghia Khe por francotiradores del Vietminh que realizan disparos de larga distancia (entre 500 y 800 metros) con fusiles Mosin Nagant M44 rusos calibre 7,62 x 54R y rifles SKS calibre 7,62 x 39 mm (entre 350 y 400 metros) y producen algunas bajas entre los conductores de los camiones que van en cabeza.

La tensión aumenta enormemente. Se teme una operación envolvente por parte de las fuerzas del Vietminh, que se hallan camufladas entre la muy profusa vegetación circundante y les aventajan notablemente en número. Además, todos ellos temen la posibilidad de ser atacados también en cualquier momento con potentes minas adosadas, cañones sin retroceso de 57 mm Tipo 36 (copias chinas del rifle sin retroceso M18A1 norteamericano) o los todavía mucho más eficaces rifles sin retroceso SKZ Sung Khong Giat de 75 mm (diseñados por Tran Dai Nghia y fabricados artesanalmente en talleres, con muy bajo coste de producción, mediante el uso de railes de acero transformados en piezas de bazooka con tolerancias inferiores a 0.5 mm) que podrían destruir los tanques de la columna francesa.

Pocos kilómetros más adelante, aguardan junto a un tramo del río Rojo (Sông Hông) a que la fuerza francesa formada por 2.000 hombres y 200 vehículos a motor (incluyendo camiones, jeeps y tanques) sea transbordada en ferry al otro lado de esta gran vía fluvial.

Tras cruzar el río, la columna de tropas francesas avanza en dirección a la Provincia de Thai Binh, internándose en su región de Vu Thu, y aproximadamente a las 8:40 h de la mañana

son atacados en el tramo de carretera entre Bong Dien y Nghia Khe por francotiradores del Vietminh que realizan disparos de larga distancia (entre 500 y 800 metros) con fusiles Mosin Nagant M44 rusos calibre 7,62 x 54R y rifles SKS calibre 7,62 x 39 mm (entre 350 y 400 metros) y producen algunas bajas entre los conductores de los camiones que van en cabeza.

La tensión aumenta enormemente. Se teme una operación envolvente por parte de las fuerzas del Vietminh, que se hallan camufladas entre la muy profusa vegetación circundante y les aventajan notablemente en número. Además, todos ellos temen la posibilidad de ser atacados también en cualquier momento con potentes minas adosadas, cañones sin retroceso de 57 mm Tipo 36 (copias chinas del rifle sin retroceso M18A1 norteamericano) o los todavía mucho más eficaces rifles sin retroceso SKZ Sung Khong Giat de 75 mm (diseñados por Tran Dai Nghia y fabricados artesanalmente en talleres, con muy bajo coste de producción, mediante el uso de railes de acero transformados en piezas de bazooka con tolerancias inferiores a 0.5 mm) que podrían destruir los tanques de la columna francesa.

Pero el general Nguyên Giáp, gran maestro de logística del

Vietminh y hombre de enorme inteligencia, no desea masacrar a las tropas

francesas mediante batalla campal en campo abierto, por dos motivos

principales:

a) Las tropas francesas están bien armadas con armas automáticas y semiautomáticas y disponen de algunos tanques. Además, sus oficiales pertenecen a la Legión Francesa, una unidad de élite, por lo que un combate masivo de tal naturaleza haría inevitable un elevado número de bajas en sus propias filas. De hecho, un año antes, el Vietminh había lanzado un ataque integral contra Nà Sâng durante la primavera de 1953, y tras feroz lucha y muy abundantes soldados muertos por ambos bandos, prevaleció la superioridad material francesa en sinergia con la defensa de erizo diseñada por el coronel Jean Gilles.

b) Giáp sabe que durante la primera semana de Mayo de 1954 Francia estudió la posibilidad de lanzar un ataque aéreo masivo contra las posiciones del Viet Minh en las colinas próximas a Dien Bien Phu con bombarderos y cazas (de hecho, las fuerzas del Viet Minh han sido atacadas frecuentemente por cazas P-63 - entre 1949 y principios de 1951-, F8F Bearcats y F6F Hellcats - entre Marzo de 1951 y el momento presente en Mayo de 1954- y aviones de transporte C-119 Flying Boxcars modificados, todos ellos comprados a Estados Unidos, que llevan varios años lanzándoles bombas y napalm como apoyo a las fuerzas terrestres galas), e incluso la Operación Vulture, diseñada para destruir por completo a las fuerzas del Viet Minh que sitiaron Dien Bien Phu, incluyendo la posibilidad de un ataque nuclear con tres bombas atómicas contra las fuerzas de Nguyên Giáp ubicadas alrededor de Dien Bien Phu para romper el cerco, pero finalmente se impuso el buen criterio del Presidente Dwight W. Eisenhower y Estados Unidos no apoyó tal iniciativa.

Además, los servicios de inteligencia de Estados Unidos habían constatado que Nguyên Giáp había contemplado con anticipación la posibilidad de un brutal ataque aéreo contras sus fuerzas bien con bombas convencionales o atómicas, por lo que había hecho avanzar a gran velocidad las líneas de trincheras del Viet Minh hacia los diferentes puntos fuertes franceses de defensa en Dien Bien Phu, hasta que estuvieron a muy pocos metros de distancia de ellos, de tal manera que desde finales de Abril de 1954 a Francia le habría sido imposible llevar a cabo ningún ataque aéreo masivo capaz de separar la propia fortaleza con soldados franceses y argelinos dentro del radio de acción de la explosión de bombas convencionales o nucleares que pudieran lanzarles

Al mismo tiempo, Giáp sabe que la gran victoria de Dien Bien Phu significó un muy alto coste en vidas humanas para sus hombres, especialmente al capturar los baluartes de Beatrice, Gabrielle e Isabelle (las más importantes zonas defensivas de Dien Bien Phu), que fueron defendidas con gran valor por los soldados profesionales franceses contra las fuerzas del Viet Minh que les superaban ampliamente en número.

Finalmente no se hizo y Diem Bien Phu cayó en manos del Viet Minh el 7 de Mayo de 1954, pero el muy experimentado general vietnamita sabe que si da orden de masacrar la columna francesa mediante un ataque en masa, quienes han organizado la Guerra de Indochina para ganar dinero, tendrían un nuevo pretexto para incrementar la escalada bélica e incluso plantear de nuevo la posibilidad de bombardeos de alfombra o bien un ataque nuclear que tendría consecuencias desastrosas para el pueblo vietnamita, por lo que opta por una guerra de guerrillas basada en ataques efectivos en momentos puntuales mediante francotiradores y morteros, que vayan mermando progresivamente la moral del enemigo, incrementando su fatiga, haciéndoles sentir en todo momento que están siendo observados y que podrían ser aniquilados en cualquier momento, con un mensaje claro: Vietnam es nuestro país, es una guerra que no podéis ganar, marcháos cuanto antes.

b) Giáp sabe que durante la primera semana de Mayo de 1954 Francia estudió la posibilidad de lanzar un ataque aéreo masivo contra las posiciones del Viet Minh en las colinas próximas a Dien Bien Phu con bombarderos y cazas (de hecho, las fuerzas del Viet Minh han sido atacadas frecuentemente por cazas P-63 - entre 1949 y principios de 1951-, F8F Bearcats y F6F Hellcats - entre Marzo de 1951 y el momento presente en Mayo de 1954- y aviones de transporte C-119 Flying Boxcars modificados, todos ellos comprados a Estados Unidos, que llevan varios años lanzándoles bombas y napalm como apoyo a las fuerzas terrestres galas), e incluso la Operación Vulture, diseñada para destruir por completo a las fuerzas del Viet Minh que sitiaron Dien Bien Phu, incluyendo la posibilidad de un ataque nuclear con tres bombas atómicas contra las fuerzas de Nguyên Giáp ubicadas alrededor de Dien Bien Phu para romper el cerco, pero finalmente se impuso el buen criterio del Presidente Dwight W. Eisenhower y Estados Unidos no apoyó tal iniciativa.

Además, los servicios de inteligencia de Estados Unidos habían constatado que Nguyên Giáp había contemplado con anticipación la posibilidad de un brutal ataque aéreo contras sus fuerzas bien con bombas convencionales o atómicas, por lo que había hecho avanzar a gran velocidad las líneas de trincheras del Viet Minh hacia los diferentes puntos fuertes franceses de defensa en Dien Bien Phu, hasta que estuvieron a muy pocos metros de distancia de ellos, de tal manera que desde finales de Abril de 1954 a Francia le habría sido imposible llevar a cabo ningún ataque aéreo masivo capaz de separar la propia fortaleza con soldados franceses y argelinos dentro del radio de acción de la explosión de bombas convencionales o nucleares que pudieran lanzarles

Al mismo tiempo, Giáp sabe que la gran victoria de Dien Bien Phu significó un muy alto coste en vidas humanas para sus hombres, especialmente al capturar los baluartes de Beatrice, Gabrielle e Isabelle (las más importantes zonas defensivas de Dien Bien Phu), que fueron defendidas con gran valor por los soldados profesionales franceses contra las fuerzas del Viet Minh que les superaban ampliamente en número.

Finalmente no se hizo y Diem Bien Phu cayó en manos del Viet Minh el 7 de Mayo de 1954, pero el muy experimentado general vietnamita sabe que si da orden de masacrar la columna francesa mediante un ataque en masa, quienes han organizado la Guerra de Indochina para ganar dinero, tendrían un nuevo pretexto para incrementar la escalada bélica e incluso plantear de nuevo la posibilidad de bombardeos de alfombra o bien un ataque nuclear que tendría consecuencias desastrosas para el pueblo vietnamita, por lo que opta por una guerra de guerrillas basada en ataques efectivos en momentos puntuales mediante francotiradores y morteros, que vayan mermando progresivamente la moral del enemigo, incrementando su fatiga, haciéndoles sentir en todo momento que están siendo observados y que podrían ser aniquilados en cualquier momento, con un mensaje claro: Vietnam es nuestro país, es una guerra que no podéis ganar, marcháos cuanto antes.

Los carros de combate franceses de la columna abren

fuego, pero la enorme capacidad de camuflaje con el terreno de los guerrilleros

del Viet Minh y su gran velocidad de movimientos hace muy difícil su localización.

Por otra parte, la temperatura roza los 40º C, con

sensación térmica próxima a los 48º C debido a los muy elevados niveles de

humedad de Vietnam. Así pues, el calor es asfixiante, y los 2.000 soldados y

oficiales de la columna sudan a mares, al igual que Capa, Mecklin y Lucas.

Tras varios minutos de tensa espera, la columna se pone

de nuevo en marcha, pero una vez más, es atacada pocos kilómetros más adelante,

en el tramo de carretera entre Thuong Dien y La Dien próximo al río Song Mu Khe, cuando uno de los camiones cruza sobre una mina y la explosión produce cuatro muertos y séis heridos.

en el tramo de carretera entre Thuong Dien y La Dien próximo al río Song Mu Khe, cuando uno de los camiones cruza sobre una mina y la explosión produce cuatro muertos y séis heridos.

A partir de aquí, el Viet Minh aumenta su presión

sobre la columna, a su paso entre las zonas de Hoa Binh y Song An, con fuego de

morteros artesanales norvietnamitas de 60 mm y 81 mm y ruso de 82 mm y francotiradores equipados con fusiles Mosin Nagant y

rifles SKS que producen varias bajas en la zona trasera.

Una vez más, los blindados franceses abren fuego, al igual que muchos soldados galos con sus subfusiles Mat-49, rifles Mas 36 y Mas 49 y carabinas M1 Garand, pero con escasa efectividad, ya que resulta virtualmente imposible localizar a los guerrilleros del Vietminh, debido a la muy abundante vegetación que les rodea, por lo que sólo consiguen incendiar varios pueblos adyacentes.

Una vez más, los blindados franceses abren fuego, al igual que muchos soldados galos con sus subfusiles Mat-49, rifles Mas 36 y Mas 49 y carabinas M1 Garand, pero con escasa efectividad, ya que resulta virtualmente imposible localizar a los guerrilleros del Vietminh, debido a la muy abundante vegetación que les rodea, por lo que sólo consiguen incendiar varios pueblos adyacentes.

Durante todo el tiempo, Capa ha estado haciendo

fotos, moviéndose rápidamente de un lado a otro, y tanto Mecklin como Lucas han

podido comprobar como su gran experiencia (veterano de cinco guerras) hace que

asuma riesgos sólo cuando siente que puede hacer una buena foto.

La columna sigue avanzando, atraviesan las zonas de

Vu Phúc y Vu Hoy y penetran en la Región de Kien Xuong (Provincia de Thai

Binh),

siguiendo la columna rumbo este entre la zona de Vu Qúy y el río Kien Giang, hasta que llegan al fuerte de Dongquithon, donde son informados de que habrá una demora de varias horas, ya que el Vietminh ha cortado la carretera pocos cientos de metros más adelante con varias anchas y profundas trincheras y ha volado los accesos a dos puentes.

siguiendo la columna rumbo este entre la zona de Vu Qúy y el río Kien Giang, hasta que llegan al fuerte de Dongquithon, donde son informados de que habrá una demora de varias horas, ya que el Vietminh ha cortado la carretera pocos cientos de metros más adelante con varias anchas y profundas trincheras y ha volado los accesos a dos puentes.

Capa se dirige rápidamente a la zona delantera de la

columna y fotografía a los bulldozers y a doscientos prisioneros del Vietminh

mientras reparan la carretera.

El oficial francés del fuerte de Dongquithon invita

a Capa, Mecklin y Lucas a almorzar en el fuerte, pero Capa decide seguir

haciendo fotos durante un rato.

Poco después, bañado en sudor y exhausto, se tumba

en el suelo a la sombra de un camión, donde Mecklin y Lucas le encuentran a las 14:00 h de la tarde.

Varios minutos después, se enteran de que los

vehículos más avanzados de la columna han llegado ya al fuerte de Doaithan, por

lo que suben a su jeep y esquivando al resto de vehículos y blindados de la

columna, llegan al pequeño y deteriorado fuerte de Doaithan, rodeado de alambre

de espino y abundante vegetación, a las 14:25 h de la tarde, constatando que

está ya siendo abandonado por su guarnición y que se están poniendo explosivos

en su estructura almenada.

La columna prosigue su marcha y 200 metros más

adelante, una nueva emboscada por parte del Viet Minh produce varias bajas

entre las tropas francesas.

El calor es insoportable y hace ya rato que la fatiga ha hecho presa entre los 2.000 hombres de la columna.

El calor es insoportable y hace ya rato que la fatiga ha hecho presa entre los 2.000 hombres de la columna.

Capa pregunta al teniente coronel Jean Lacapelle si

ha habido novedades, y éste le responde que el Vietminh está por todas partes.

Capa está agotado, pero su amor por la profesión y

su lucha constante por sacar nuevas y mejores fotos, hacen que decida saltar

sobre la parte delantera del jeep para conseguir imágenes desde un ángulo

distinto, algo elevado.

La columna avanza de nuevo con dirección este, pero

una vez más se ve obligada a detenerse por la acción combinada de

francotiradores equipados con carabinas SKS y fusiles Mosin Nagant M44 y

dotaciones de morteros rusos M1937, M1941 and M1943 de 82 mm, y morteros norvietnamitas de 60 mm y 81 mm fabricados artesanalmente en talleres ubicados en las montañas con herramientas transferidas de la fábrica Caron de Haiphong bajo la supervisión del ingeniero Tran Dai N´Ghia, máximo experto de Vietnam en tecnología militar, que ha estudiado en la Escuela Politécnica y la Escuela Superior Aeronáutica de París, y cuyo talento ha permitido producir muchas armas efectivas con presupuestos muy bajos y escasos medios, incluyendo una más que aceptable copia del mortero americano M1 de 81 mm y su munición M43A1 de 3,11 kilos y el mortero de 60 mm Tipo 31 (optimizado para portabilidad, una copia del M2 norteamericano creada por Tran Dai N´Ghia reduciendo costes al máximo y con una pérdida de alcance efectivo de sólo 300 metros) y el mortero de 60 mm Tipo 63 (una versión actualizada del Tipo 31 en la que el científico vietnamita consiguió también reducir costes acortando la longitud del cañón 11´64 cm con respecto al M2).

Están siendo atacados desde diferentes distancias, ya que los snipers del Vietminh ubicados a ambos lados de la carretera, les disparan desde entre 350 y 400 metros los que llevan carabinas SKS y entre 500 y 800 metros los que usan Mosin Nagant M44 con mira telescópica larga, mientras que por su parte, las dotaciones de mortero del Viet Minh poseen una enorme experiencia y pericia en el manejo de este arma, siendo capaces de determinar el azimut de fuego y sus ajustes de elevación en muy pocos segundos, disparando sus obuses de 60, 81 y 82 mm con gran precisión y efectividad y cambiando rápidamente de posición.

Están siendo atacados desde diferentes distancias, ya que los snipers del Vietminh ubicados a ambos lados de la carretera, les disparan desde entre 350 y 400 metros los que llevan carabinas SKS y entre 500 y 800 metros los que usan Mosin Nagant M44 con mira telescópica larga, mientras que por su parte, las dotaciones de mortero del Viet Minh poseen una enorme experiencia y pericia en el manejo de este arma, siendo capaces de determinar el azimut de fuego y sus ajustes de elevación en muy pocos segundos, disparando sus obuses de 60, 81 y 82 mm con gran precisión y efectividad y cambiando rápidamente de posición.

Capa percibe claramente el enorme peligro y que el Viet Minh

domina claramente la situación disparando desde los bosques adyacentes,

camuflados entre la maleza y sin necesidad de forzar un choque masivo de

fuerzas, manteniendo la iniciativa con respecto a donde y cuando atacar, teniendo a la columna francesa bajo constante observación desde puntos específicos, moviéndose con gran velocidad y seleccionando los tramos de terreno más propicios para las contínuas emboscadas que van minando la moral del enemigo, arreglándoselas a la vez para ocultarse entre la espesa vegetación para evitar ser detectados desde tierra o aire, y llevando la iniciativa táctica en todo momento.

No es la primera vez que Bob presencia un contexto

de ataque con fuego de morteros, algo que ya le ocurrió en Diciembre de 1944

cuando iba empotrado entre los tanques del Batallón 37 de la 4ª División

Acorazada de Estados Unidos que se abrieron paso hacia Bastogne para ayudar a

la 101ª División Aerotransportada rodeada por fuerzas alemanas durante la

Batalla de las Ardenas, y especialmente un año antes, el 30 de Diciembre de

1943, mientras acompañaba a los elementos de vanguardia del 180º Regimiento de

la 45ª División de Estados Unidos durante un ataque sobre Venafro, estratégico municipio

italiano de la provincia de Isernia, región de Molise (Italia), cuando de

repente fueron atacados con fuego de mortero alemán, que mató a un soldado

norteamericano que estaba a su lado, a consecuencia del impacto de tres

fragmentos de metralla.

Pero aún consciente de que el riesgo es muy elevado,

Capa sigue haciendo fotos, moviéndose rápidamente de un lado a otro. Mecklin y

Lucas observan cómo Capa arriesga su vida por enésima vez, intentando conseguir

las mejores imágenes posibles.

Se escuchan claramente los silbidos de balas del

calibre 7,62 x 39 y 7.62 x 54R disparadas por los francotiradores del Viet Minh

que continúan produciendo bajas, así como las explosiones de los proyectiles de 60 mm, 81 mm y 82 mm lanzados por los morteros del Viet Minh, que están provocando el

pánico.

Han dejado Doithan 1 km atrás, y se encuentran a tan sólo 3 km de distancia de Thanh Ne, el objetivo final.

Han dejado Doithan 1 km atrás, y se encuentran a tan sólo 3 km de distancia de Thanh Ne, el objetivo final.

La tensión es máxima. De repente, Mecklin y Lucas

ven que Bob regresa corriendo al jeep y se refugia junto a uno de sus lados. Mira a

los bosques próximos y escudriña la trayectoria de los disparos de fusil y

mortero del Viet Minh que se están produciendo.

El fotógrafo se mantiene

agazapado tras el vehículo, tratando de protegerse de una posible bala de francotirador o de la

metralla de un proyectil de mortero, siendo éste último el factor de riesgo más temido, ya que los obuses de morteros de 60 mm Tipo 31 y 63 del Vietminh tienen un radio de acción letal de aproximadamente 22 metros en el momento de su explosión, mientras que sus morteros de 81 y 82 mm lanzan proyectiles con un alcance mortífero de 35 metros en derredor al estallar.

La adrenalina se multiplica exponencialmente. Una lluvia de balas de fusil y carabina y proyectiles de mortero disparados por el Viet Minh está cayendo sobre la columna francesa en la que Capa se halla incrustado. Esto es un auténtico infierno. El

fotógrafo sabe que hay que jugársela. No en vano, desde hace ya dieciocho años, cuando tuvo su bautismo de fuego durante la Guerra Civil Española, éste es su biotopo.

Durante toda su carrera profesional como fotoperiodista, Robert Capa añadió continuamente un lado humano a sus potentes instantáneas de guerra. Sus conmovedoras e impactantes imágenes son todavía en gran medida la referencia en el ámbito de la fotografía comprometida. Y allí donde fue, siempre consiguió conectar con la gente, generando una sincera empatía. El objetivo más importante en el que centró gran parte de sus esfuerzos durante toda su vida fue conseguir la independencia de los fotógrafos, que debían poseer sus negativos originales y podrían vender sus fotografías a diferentes publicaciones a la vez, controlando su obra y haciéndose respetar.

De hecho, su vida entera ha sido una partida de póker, sin casa fija, sin patria, siempre errante y siempre luchando por la supervivencia, desde que con tan sólo 17 años se convirtió en un exiliado político que tuvo que huir de Budapest la mañana del 12 de Julio de 1931 y dirigirse a Berlín, de donde tendría que marchar también posteriormente huyendo del antisemitismo nazi.

Durante toda su carrera profesional como fotoperiodista, Robert Capa añadió continuamente un lado humano a sus potentes instantáneas de guerra. Sus conmovedoras e impactantes imágenes son todavía en gran medida la referencia en el ámbito de la fotografía comprometida. Y allí donde fue, siempre consiguió conectar con la gente, generando una sincera empatía. El objetivo más importante en el que centró gran parte de sus esfuerzos durante toda su vida fue conseguir la independencia de los fotógrafos, que debían poseer sus negativos originales y podrían vender sus fotografías a diferentes publicaciones a la vez, controlando su obra y haciéndose respetar.

De hecho, su vida entera ha sido una partida de póker, sin casa fija, sin patria, siempre errante y siempre luchando por la supervivencia, desde que con tan sólo 17 años se convirtió en un exiliado político que tuvo que huir de Budapest la mañana del 12 de Julio de 1931 y dirigirse a Berlín, de donde tendría que marchar también posteriormente huyendo del antisemitismo nazi.

Capa decide salir de la protección del jeep y sigue

haciendo fotos a gran velocidad, asumiendo riesgos que su experiencia le

permite calcular si la oportunidad de obtener buenas fotos así lo exige, pero

siempre con el factor de incertidumbre y azar presentes, que pueden provocar la

muerte, de repente y de modo inesperado, en cualquier momento.

Desde hace varios minutos, las tropas francesas avanzan

a través de un gran arrozal ubicado a la izquierda de la carretera que conduce

a Thahn Né. Caminan lentamente, con mucha cautela, y algunos de ellos llevan

detectores de minas. Y pese al asfixiante calor, todos los soldados están con

sus cascos puestos por temor a disparos en la cabeza de los francotiradores del

Vietminh.

Capa, que lleva dos cámaras telemétricas (una Contax

IIa Black Dial formato 24 x 36 mm hecha en la fábrica Zeiss Ikon A.G de Stuttgart (Alemania Federal) con objetivo Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 50 mm f/2 T y película monocroma Kodak Super-XX High Speed ISO 250 y una Nippon Kogaku Nikon S formato 24 x 34 mm con objetivo Nikkor-S.C 5 cm f/1.4 y película de color Kodachrome K-11 ISO 12 ) les hace varias

fotografías desde distintos ángulos, la mayoría en blanco y negro.

Faltan aproximadamente cinco minutos para las 15:00 h de la tarde y Capa hace sus dos últimas fotografías:

Faltan aproximadamente cinco minutos para las 15:00 h de la tarde y Capa hace sus dos últimas fotografías:

a) Una en color con su Nikon S en la que capta desde

atrás a 17 soldados de la columna francesa (uno de ellos, situado a la

izquierda de la imagen es un soldado de transmisiones equipado con radio,

mientras que el situado a la derecha más próximo a la cámara lleva un detector

de minas) así como un tanque que se vislumbra al fondo ligeramente a la

derecha.

© Robert Capa / ICP New York.

A la derecha de la imagen se aprecia el dique de un arroyo que fluye a la derecha así como su ligera pendiente que lleva hasta la carretera.

© Robert Capa / ICP New York.

A la derecha de la imagen se aprecia el dique de un arroyo que fluye a la derecha así como su ligera pendiente que lleva hasta la carretera.

b) Otra en blanco y negro hecha con su Contax IIa en la

que capta también desde atrás a nueve soldados de la columna francesa. Esta es

la última foto hecha por Capa, segundos antes de pisar la mina, ubicada en la

pendiente que se aprecia a la derecha justo tras el pequeño dique, una zona que casi 60 años después está cubierta de árboles y espesa vegetación.

© Robert Capa / ICP New York.

Puede observarse que con respecto a la foto previa en color, Capa ha avanzado rápidamente en diagonal hacia la derecha, buscando hacer una foto desde un ángulo distinto y en la que tanto soldados como el blindado llenen más el encuadre, de tal manera que dicho carro de combate que en la imagen anterior en color aparece ligeramente a la derecha de la zona central del encuadre, ahora es visible a la izquierda del todo del encuadre, mientras que tanto el pequeño dique como la suave pendiente tras él aparecen mucho más próximos.

© Robert Capa / ICP New York.

Puede observarse que con respecto a la foto previa en color, Capa ha avanzado rápidamente en diagonal hacia la derecha, buscando hacer una foto desde un ángulo distinto y en la que tanto soldados como el blindado llenen más el encuadre, de tal manera que dicho carro de combate que en la imagen anterior en color aparece ligeramente a la derecha de la zona central del encuadre, ahora es visible a la izquierda del todo del encuadre, mientras que tanto el pequeño dique como la suave pendiente tras él aparecen mucho más próximos.

A continuación, Capa decide avanzar hacia la

pendiente, probablemente con la intención de sacar más fotos desde una posición

más elevada, y al comenzar a subir por ella pisa una mina antipersonal que había sido colocada durante la noche por el Viet Minh, que tenía un profundo conocimiento del terreno.

La explosión le arranca la pierna izquierda

prácticamente de cuajo y le abre una enorme herida en el pecho.

La onda

expansiva lanza su Nikon S a varios metros de distancia (el fotoperiodista

norteamericano Sal di Marco pudo ver a principios de los años setenta manchas

de sangre en esta cámara que estuvo expuesta en la antigua Nikon House de Nueva

York, y que es hoy en día propiedad de la Nikon Historical Society), mientras Capa, inconsciente y tumbado de espaldas sobre el suelo, tiene

su mano izquierda aferrada a su cámara Contax IIa con la que ha hecho su última

foto, en blanco y negro.

Mecklin y Lucas llegan al lugar de la explosión a las 15:10 h. Capa ha perdido mucha sangre y está agonizando. De repente, llega el coronel Lacapelle, que ha oído la deflagración. Ve a Capa en el suelo y llama rápidamente a una ambulancia que se lleva a Capa al puesto de primeros auxilios más cercano ubicado en el fuerte de Dongquithon, 5 km atrás, donde un médico vietnamita certifica la muerte de Robert Capa.

Mecklin y Lucas llegan al lugar de la explosión a las 15:10 h. Capa ha perdido mucha sangre y está agonizando. De repente, llega el coronel Lacapelle, que ha oído la deflagración. Ve a Capa en el suelo y llama rápidamente a una ambulancia que se lleva a Capa al puesto de primeros auxilios más cercano ubicado en el fuerte de Dongquithon, 5 km atrás, donde un médico vietnamita certifica la muerte de Robert Capa.

UN LEGADO FOTOGRÁFICO MUY VIVO

Tras la muerte de Robert Capa, los cimientos de la

Agencia Magnum, concebida por él y de la que fue su máximo impulsor, se

tambalearon, un hecho que se agravó todavía más con la muerte casi simultánea

en los Andes Peruanos del genio Werner Bischof, que era el mejor amigo de Bob junto con John G. Morris, David Seymour Chim y Csiki Weisz.

A partir de este momento, hubo una serie de personas

que se pusieron manos a la obra para continuar la obra emprendida por Robert

Capa y su defensa de los derechos de los fotógrafos y la propiedad de los

negativos originales: Henri Cartier-Bresson, David Seymour “Chim”, Cornell

Capa, John G. Morris, Inge Bondi, Margot Shore, Ernst Haas, Inge Morath,

Elliott Erwitt, Eve Arnold, Dennis Stock, Burt Glinn y muchos otros.

Al mismo tiempo, comenzó a gestarse un equipo de personas

que dedicarían muchos años de su vida a la clasificación y ordenación del

inmenso legado de Robert Capa, constituido por aproximadamente 70.000 negativos

de 35 mm y formato medio 6 x 6 cm, así como por miles de copias de época y

posteriores: Cornell Capa, su esposa Edie Schwartz y Allan Brown iniciaron la

tarea a mediados de los años cincuenta, sumándose a mediados de los sesenta

Anna Winnand (secretaria de Kornél) y James A. Fox (uno de los más importantes

editores gráficos de la historia y redactor jefe de Magnum París entre 1976 y

2000).

Todos ellos realizaron un trabajo ímprobo, cuyo fruto sería en 1975 el

nacimiento del International Center of Photography de Nueva York, en cuya

génesis también colaboró de manera importante Mischa-Bar-am.

International Center of Photography de Nueva York. Los esfuerzos constantes realizados por Cornell Capa, su mujer Edie, Allan Brown, Anna Winand, Rossellina Bischof, Eileen Shneiderman, Mischa Bar-am, James A. Fox, Richard Whelan, Brian Wallis, Willis Hartshorne, Cynthia Young, Kristen Lubben, Fritz Block, los grandes positivadores Teresa Engle Moreno e Igor Bakht, Jeffrey A. Rosen, Caryl Englander, Mark Robbins, Gayle G. Greenhill, Frederick Sievert, Stephanie H. Shuman y otros han convertido este sancta sanctorum de la fotografía del más alto nivel en el más importante referente en su ámbito a nivel mundial, y lo que comenzó siendo una institución dedicada a la preservación y difusión del legado fotográfico de Robert Capa, el genio Werner Bischof y David Seymour Chim se ha transformado en sede de grandes e históricas exhibiciones fotográficas hechas por fotógrafos de contrastada talla en los cinco continentes, además de ser hoy por hoy un centro de primerísimo nivel en la enseñanza de la fotografía, en el que se imparten abundantes cursos y seminarios.

De modo asombroso, el paso de los años ha hecho que la obra fotográfica de Robert Capa y su prestigio como fotoperiodista aumente más y más su importancia y calado cada día, hasta llegar al momento presente, cien años después de su nacimiento y casi 60 tras su muerte.

International Center of Photography de Nueva York. Los esfuerzos constantes realizados por Cornell Capa, su mujer Edie, Allan Brown, Anna Winand, Rossellina Bischof, Eileen Shneiderman, Mischa Bar-am, James A. Fox, Richard Whelan, Brian Wallis, Willis Hartshorne, Cynthia Young, Kristen Lubben, Fritz Block, los grandes positivadores Teresa Engle Moreno e Igor Bakht, Jeffrey A. Rosen, Caryl Englander, Mark Robbins, Gayle G. Greenhill, Frederick Sievert, Stephanie H. Shuman y otros han convertido este sancta sanctorum de la fotografía del más alto nivel en el más importante referente en su ámbito a nivel mundial, y lo que comenzó siendo una institución dedicada a la preservación y difusión del legado fotográfico de Robert Capa, el genio Werner Bischof y David Seymour Chim se ha transformado en sede de grandes e históricas exhibiciones fotográficas hechas por fotógrafos de contrastada talla en los cinco continentes, además de ser hoy por hoy un centro de primerísimo nivel en la enseñanza de la fotografía, en el que se imparten abundantes cursos y seminarios.

De modo asombroso, el paso de los años ha hecho que la obra fotográfica de Robert Capa y su prestigio como fotoperiodista aumente más y más su importancia y calado cada día, hasta llegar al momento presente, cien años después de su nacimiento y casi 60 tras su muerte.

De hecho, durante los últimos cinco años, entre 2009

y 2013, se han generado insólitos niveles de interés y expectación por las

fotografías realizadas por Capa durante sus 22 años de carrera profesional,

celebrándose históricas exhibiciones como This is War! Robert Capa

at Work organizada por Cynthia Young (Assistant Curator del ICP New York) con

gran esfuerzo y meticulosidad en Nueva York, Londres, Barcelona, Milan, Madrid,

etc, la exhibición Robert Capa en el Ludwig Museum de Budapest entre el 3 de

Julio y el 11 de Octubre de 2009, la exhibición Robert Capa China 1938 en la

Leica Gallery de Viena entre el 13 de Febrero de 2013 y el 13 de Abril de 2013; Capa 1943-45 en la Galerie Daniel Blau Paris Photo entre el 14 y el 17 de Noviembre de 2013; Robert Capa Retrospective en Villa Marin Passariano del Friuli (Italia) entre el 20 de Octubre de 2013 y el 19 de Enero del 2014 y el Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography entre Marzo y Junio del 2014; Robert Capa 100 en el Sejong Center for the Performing Arts de Seúl entre el 2 de Agosto y el 28 de Octubre de 2013; Robert Capa in Italy 1943-1944 en el Museo di Roma Palazzo Braschi entre el 3 de Octubre de 2013 y el 6 de Enero del 2014, que será también exhibida en el Museo Nazionale della Fotografia Fratelli Alinari de Florencia entre el 10 de Enero y el 30 de Marzo de 2014; ; la exhibición Robert Capa 100 Years que tiene lugar

en estos momentos en el Hungarian National Museum de Budapest desde el 18 de

Septiembre de 2013 y que se prolongará hasta el 12 de Enero de 2014; Capa in Colour, que se celebrará en el ICP de Nueva York antre el 31 de Enero y el 4 de Marzo de 2014 y muchas otras.

Otro gran acontecimiento que ha potenciado todavía más si cabe el legado fotográfico de Robert Capa ha sido el hallazgo de la ya famosa Maleta Mexicana, que incluye 4.500 negativos expuestos por Capa, David Seymour Chim y Gerda Taro durante la Guerra Civil Española, así como algunos expuestos por Fred Stein en París y con la que se celebraron exhibiciones en Nueva York, Arlés, el Museo Nacional de Arte de Cataluña, el Museo de Bellas Artes de Madrid y otras ciudades.

© Texto y Fotos Indicadas: José Manuel Serrano Esparza

Artículo de La Muerte de Robert Capa publicado en Revista de Fotografía FV nº 232

Otro gran acontecimiento que ha potenciado todavía más si cabe el legado fotográfico de Robert Capa ha sido el hallazgo de la ya famosa Maleta Mexicana, que incluye 4.500 negativos expuestos por Capa, David Seymour Chim y Gerda Taro durante la Guerra Civil Española, así como algunos expuestos por Fred Stein en París y con la que se celebraron exhibiciones en Nueva York, Arlés, el Museo Nacional de Arte de Cataluña, el Museo de Bellas Artes de Madrid y otras ciudades.

© Texto y Fotos Indicadas: José Manuel Serrano Esparza

Artículo de La Muerte de Robert Capa publicado en Revista de Fotografía FV nº 232

+FROM+HANOI+(VIETNAM).+Copyright+Jos%C3%A9+Manuel+Serrano+Esparza.jpg)

+SEEN+FROM+THE+BRIDGE+NEAR+THE+SPOT+WHERE+THE+FRENCH+COLUMN+WAS+FERRIED+ON+MAY+25,+1954.+Copyright+Jos%C3%A9+Manuel+Serrano+Esparza.jpg)

+FROM+HANOI+(VIETNAM).+Copyright+Jos%C3%A9+Manuel+Serrano+Esparza.jpg)

+SEEN+FROM+THE+BRIDGE+NEAR+THE+SPOT+WHERE+THE+FRENCH+COLUMN+WAS+FERRIED+ON+MAY+25,+1954.+Copyright+Jos%C3%A9+Manuel+Serrano+Esparza.jpg)